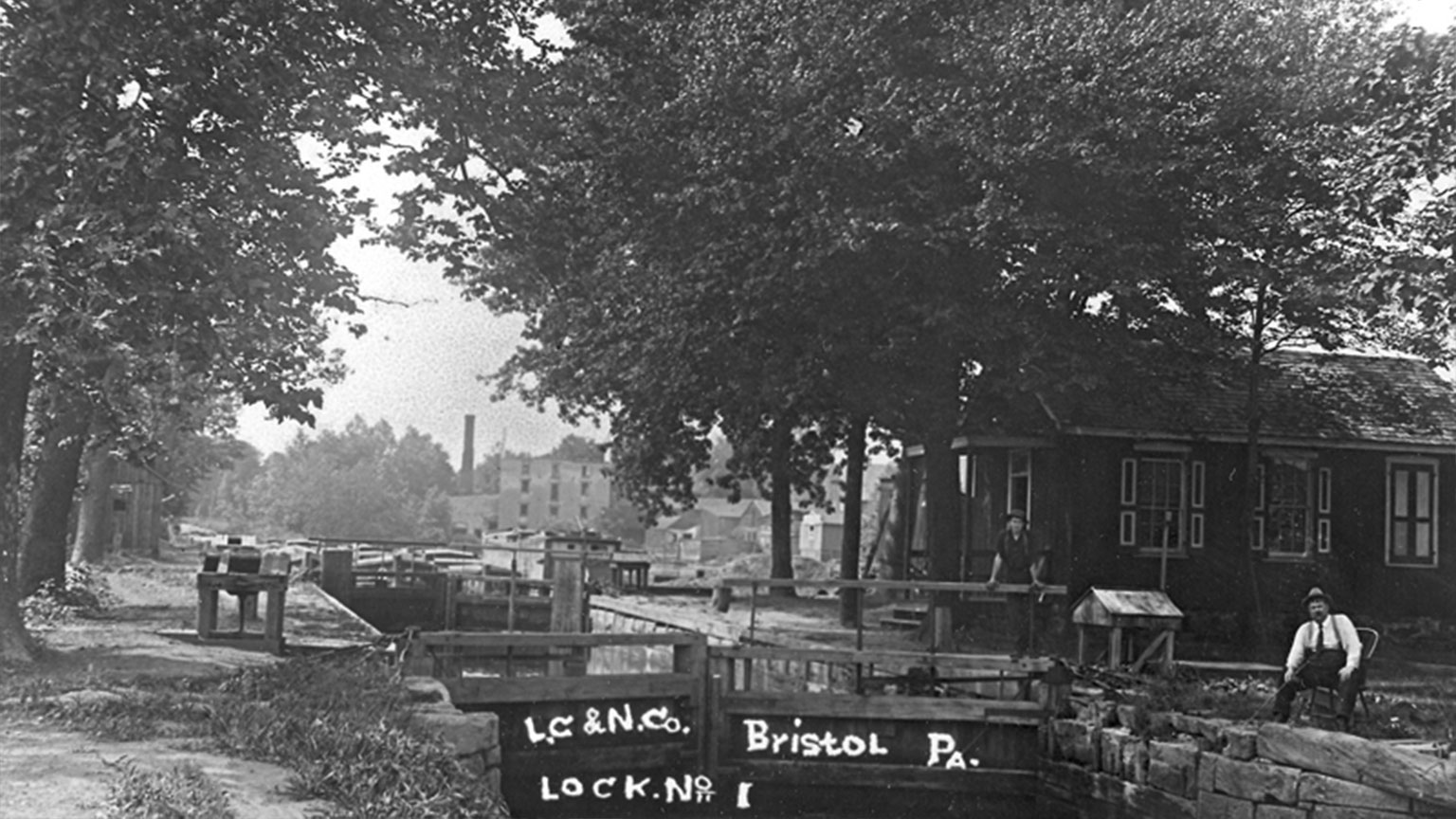

Lehigh Coal and Navigation Co.

Lehigh Coal and Navigation Co.

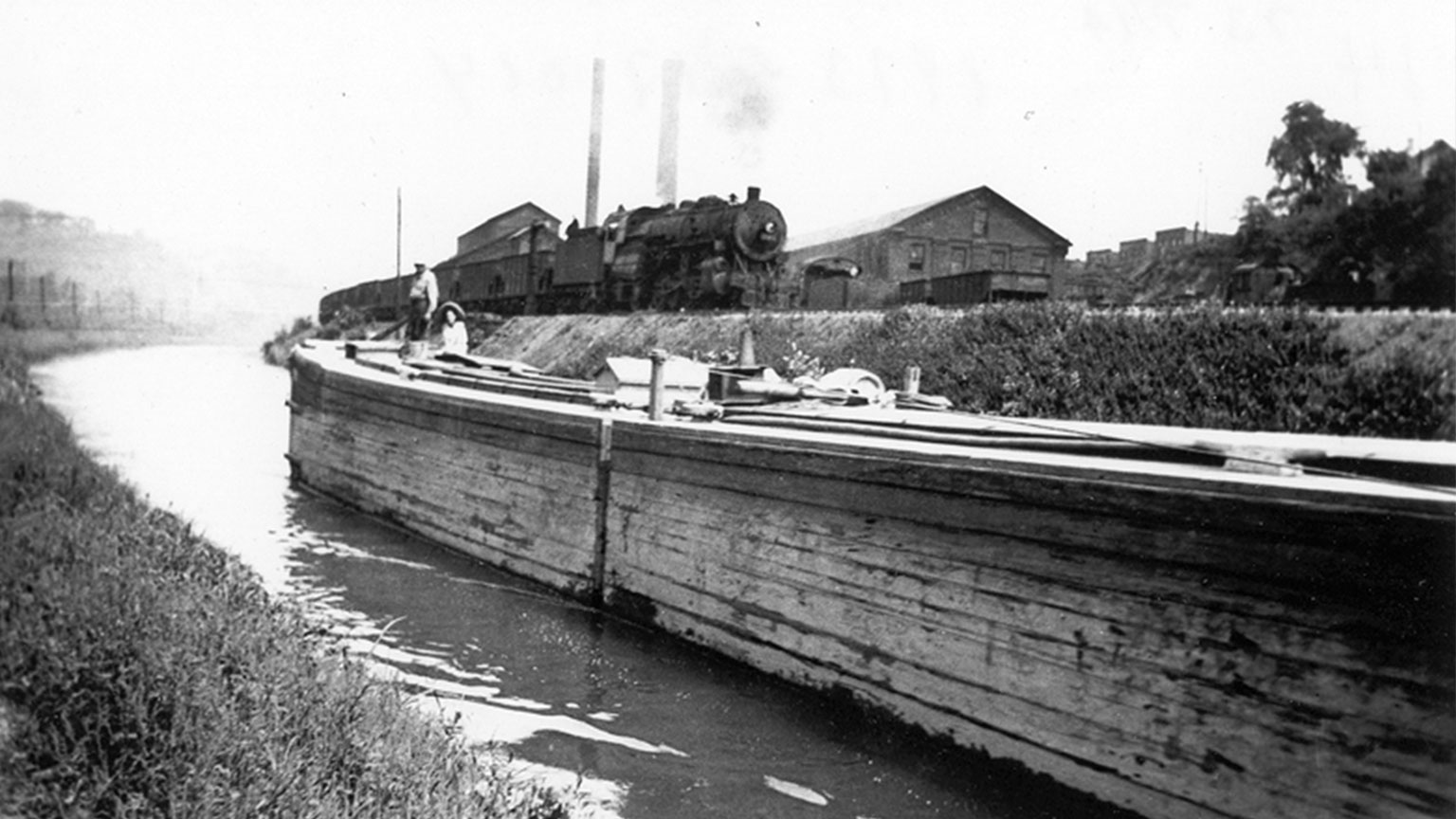

The Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company was one of the most important corporations in America's history. Its founders, Josiah White and Erskine Hazard, played a major role in the American "industrial revolution" through the company's catalytic influence on the development of anthracite coal mining, canal technology, railroads, iron production, and wire rope. They petitioned the Pennsylvania legislature to allow them to use the public Lehigh River for private use. The legislature famously said, "You may have the privilege of ruining yourselves." as no one thought that they would be able to harness the river. The first way they did this was by building “bear trap” dams, which let shallow boats loaded with coal float over the shallow, rocky parts of the Lehigh River. This allowed the company’s coal to reach markets in Philadelphia. Then the two-way Navigation canal allowed them to ship coal from the northern mines to cities and towns to the south. Building the Navigation was an engineering feat done completely with simple machines and man and animal muscle. The LC&N became very profitable, and the two canals that it ran are still around us today.

Freemansburg

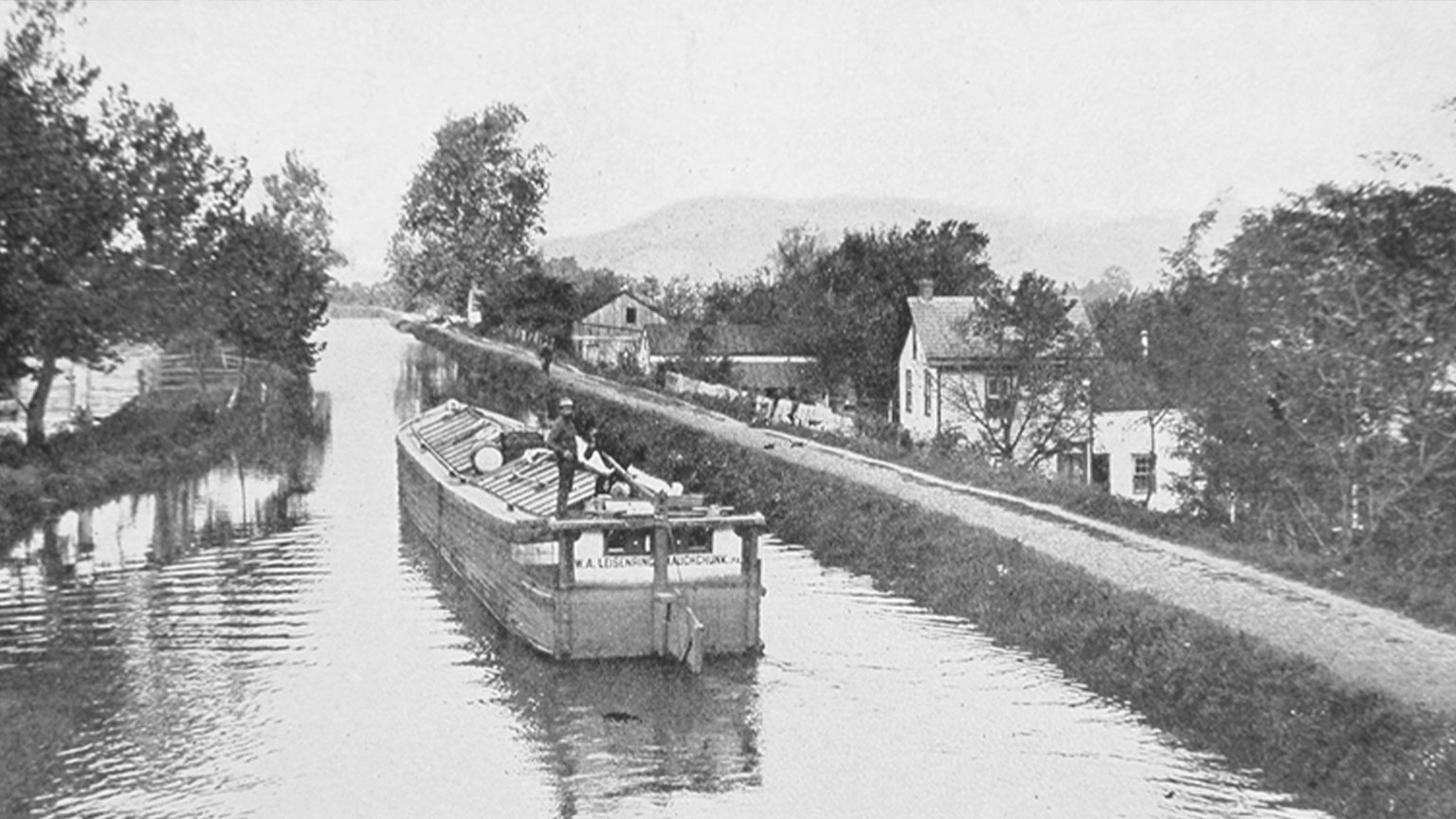

Freemansburg became a thriving canal town after the Lehigh Canal opened in the summer of 1828. In addition to hosting a steady stream of canal traffic, the busy town of 600 people was the site of three boat-building businesses that produced 80 to 100 canal boats a year until the businesses ceased operating in 1870.

Named after Jacob Freeman, Freemansburg was a hub for local farmers who brought their grains to be made into flour at a large grist mill next to Lock 44. Freemansburg also was home to coal yards, a carriage factory, saw mill, a soap and candle factory, tinsmith, and other small businesses. An early fire company was built in 1855 across Main Street from the Freeman House, a tavern that was operated by Jacob Freeman as early as 1830.

The famous Walking Purchase of 1737 crossed the Lehigh River at Jones Island at the west end of Freemansburg. Learn more about Freemansburg.

Daily Schedule

Daily life on the canal was long. It began and ended with the chores specifically for the mule driver. The mule driver would rise at 3 am to collect the mules, feed and groom them and ready them for the day. The canal boat captain or his wife or third workers would rise around this time to make breakfast and begin to prepare themselves as well. By 4 am the captain was at the tiller and they were moving on the canal. They would not stop until 10 pm. The mule tender would then spend about an hour bedding down his mules, not falling into bed himself until about 11 pm.

They did this 6 days a week. Sunday the canal was closed to observe the Sabbath and force a day of rest on the canal captains who would otherwise continue to work. This was not true for all canals, however, on the Lehigh and Delaware Canals which were run by the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Co., it was.

Remember, time was money. The more time you spent moving on the canal the faster you delivered your goods, the more money you could make. Meals were taken on the move. Breaks were given when needed and only in ways that allowed the boat to keep moving. Captains and mule tenders would trade spots for a bit or another crew member or family member would relieve the main workers as needed. The boat was in constant motion throughout the day. The crew that ran the boat was in constant states of work. It was a busy day.

Profit

The difference between the amount the canal captains would pay for a good they were taking on the canal versus what they were paid for it when they reached their destination was their profit. From the profit they then had to pay out any crew that was not part of their family, the food everyone ate, any supplies they needed for the boat, the food for the mules, fees for mule barns, tolls, and any expenses that may have popped up from any mishaps along the way such as losing a rope into the water and needing to replace it. What ever was left over the captain could pocket.

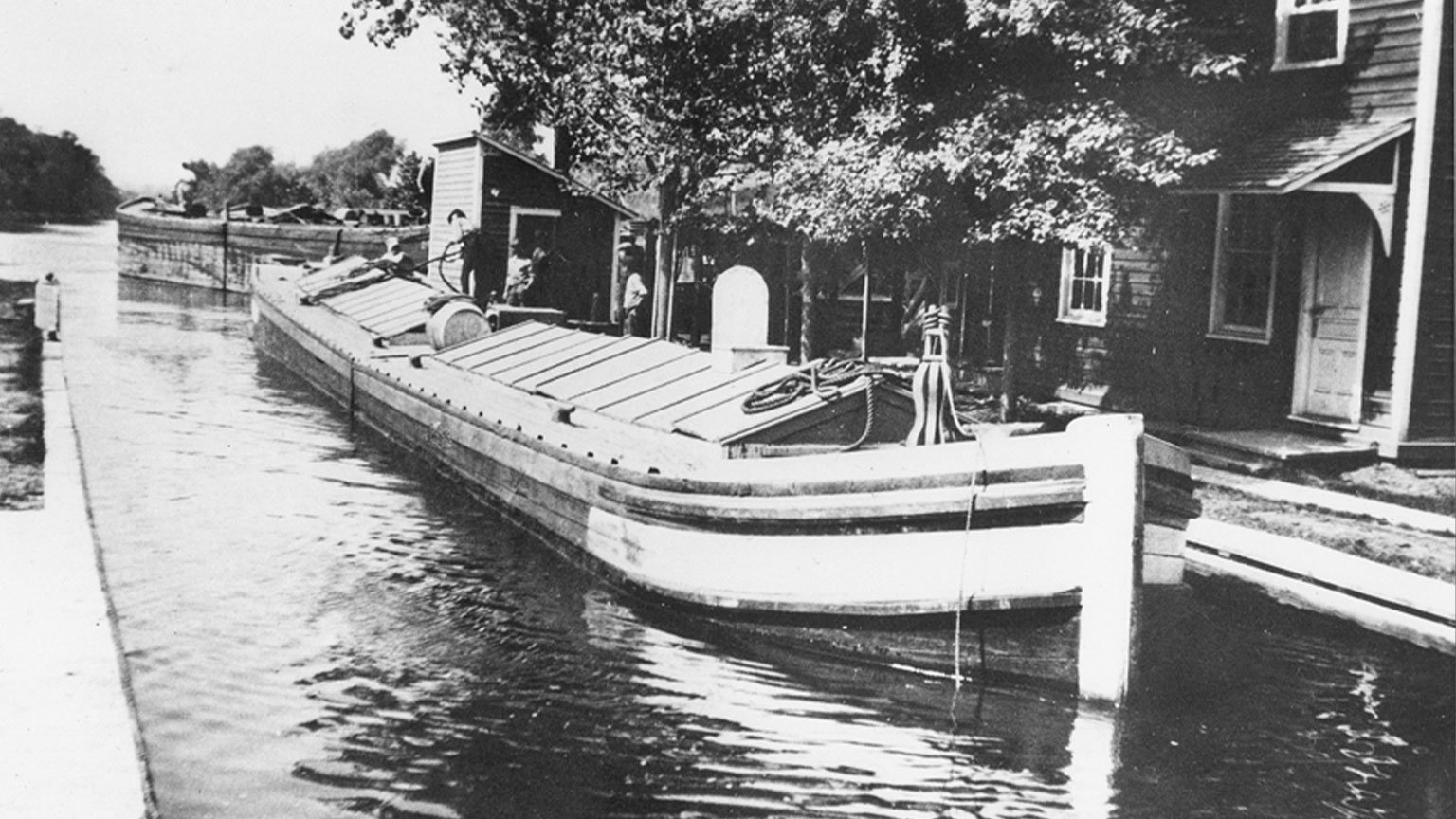

Canal Boat

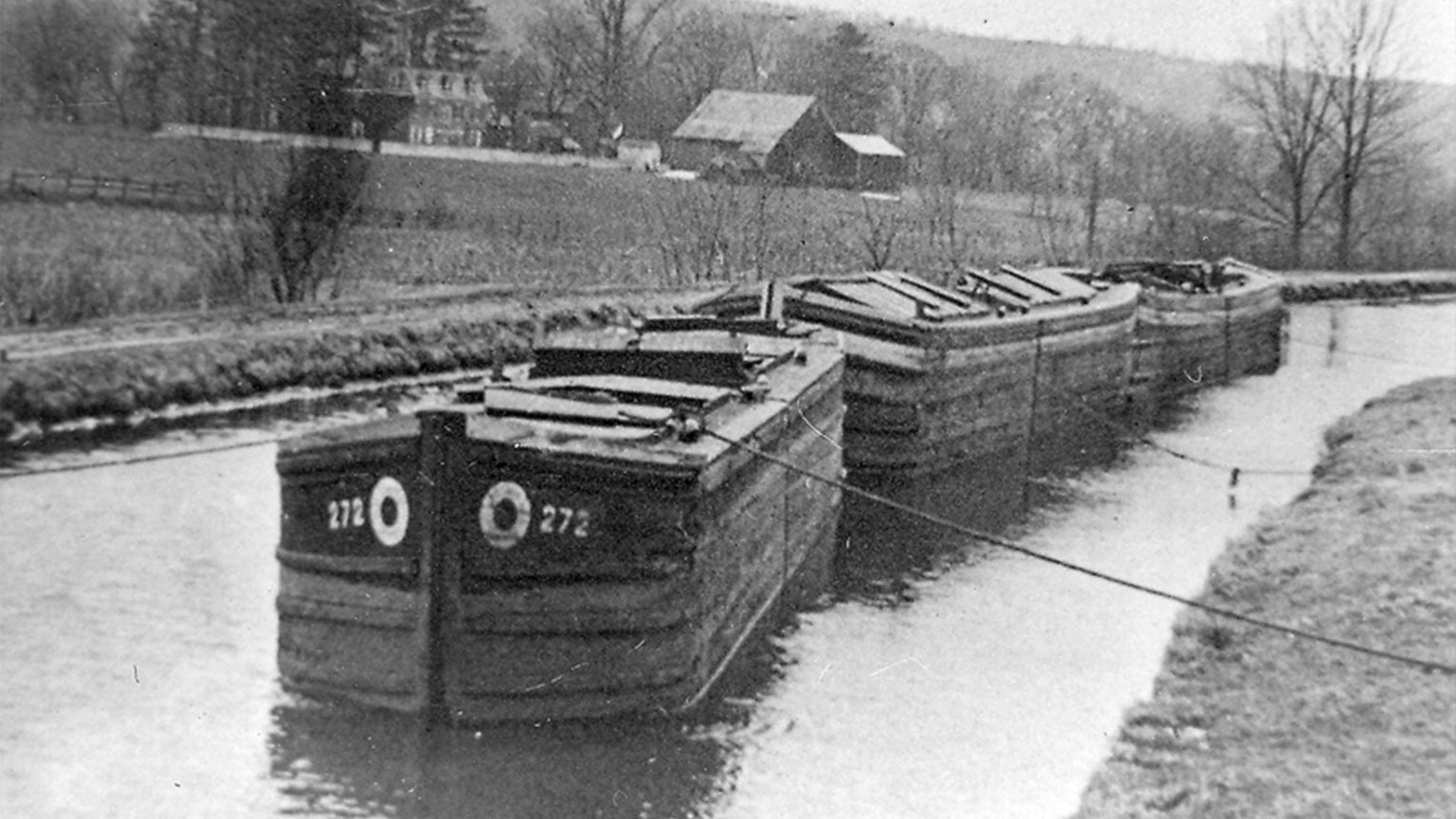

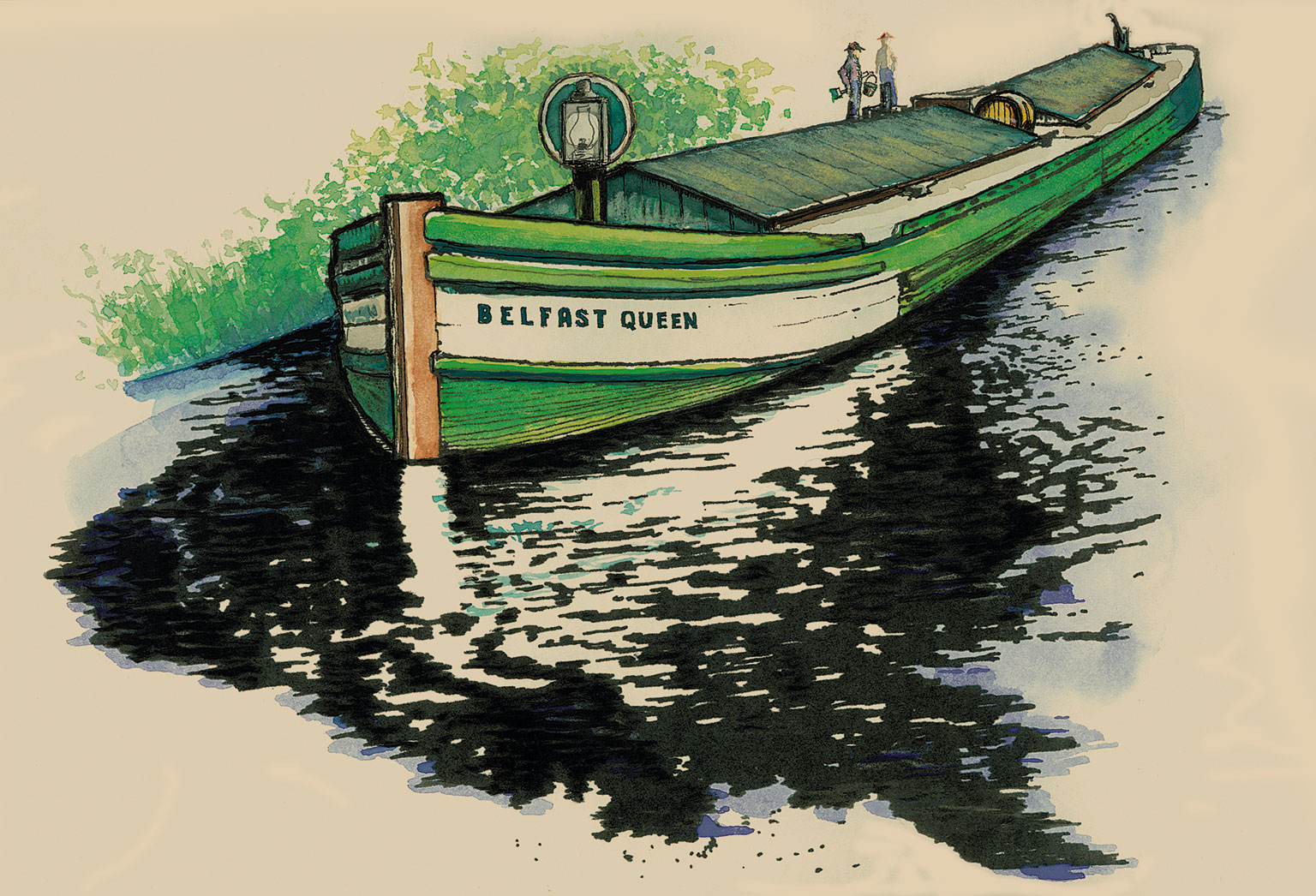

There were multiple types of canal boats that could be found along the canal systems that crisscrossed the United States. Along the Lehigh Canal, which was smaller than other canal systems, only cargo canal boats were allowed. They were a bit thinner than other canal boats as well because the canal was a bit narrower. Hinge boats were common on the Lehigh Canal because it was a great way to carry more goods in one trip. This was the type of boat that the Gormans had.

A hinge boat was a clumsy craft but particularly adapted to the coal trade of the eastern Pennsylvania canals. The boat was 87.5 feet long, 10.5 feet wide, and in cross section a perfect rectangle. The hinge boat was made in two halves which were joined together by metal fittings and pins. When the pins were removed, the two halves could be handled independently. Each half could be turned around anywhere in the canal, something that would have been difficult with a one piece boat of the same length. Normally, an 87 foot boat could be turned around only on enlarged sections of the canal called boat basins. The hinge boat also provided a means of carrying mixed cargoes of coal, such as chestnut coal in one hold and egg coal in the other. During unloading, less strain was placed on a hinge boat than would occur on a "stiff" or single boat. Hinge boats could carry up to 100 tons of coal, while a single boat's maximum load was about 60 tons.

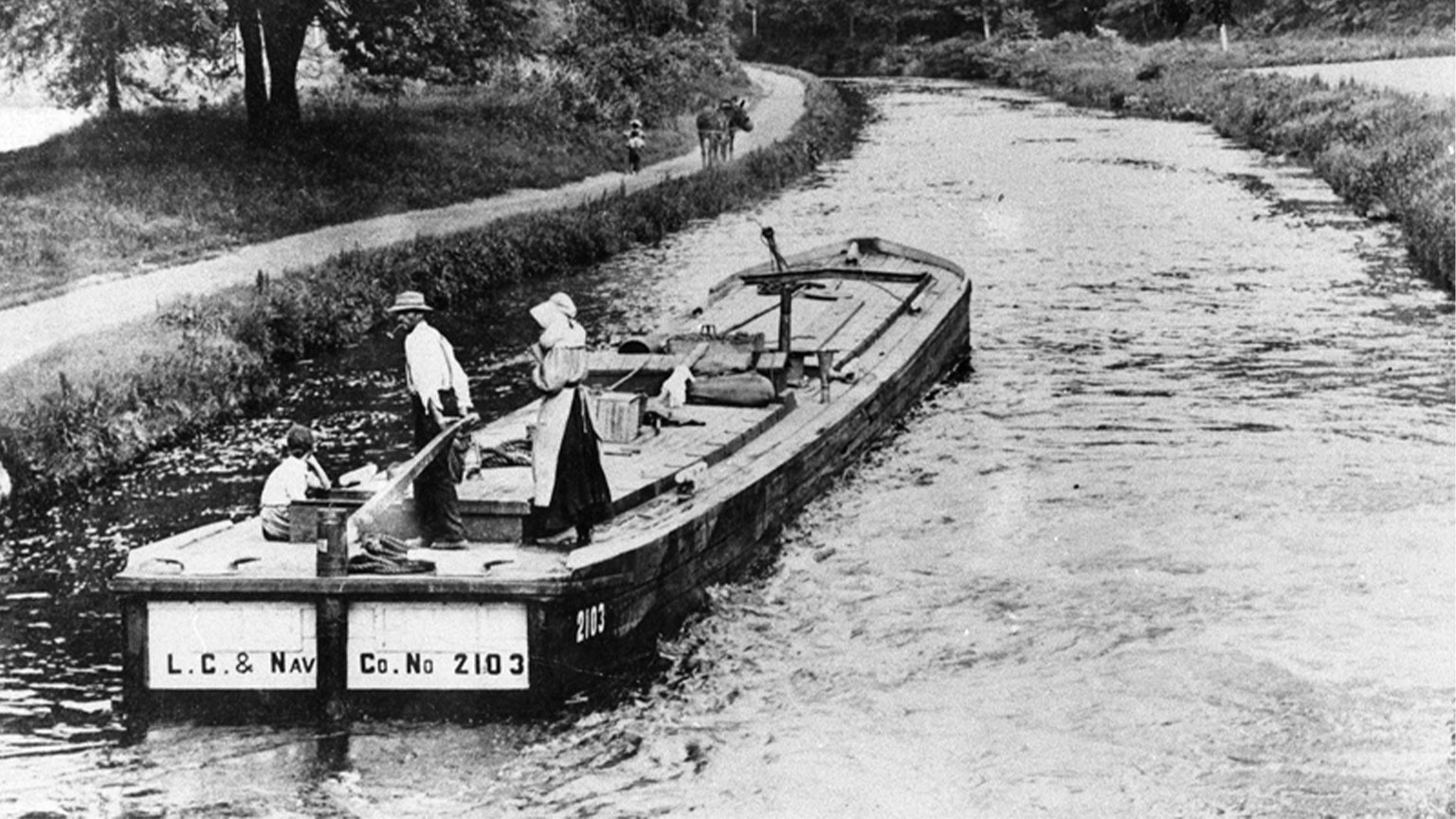

Mule Tenders

Canal boats were pulled by sturdy teams of stout-bodied mules, which walked the towpath, pulling boats laden with up to 100 tons of cargo toward the destinations. Mule tenders, also called mule drivers, often the children of the boat captains, walked with the teams. It was their job to make sure the mules kept to the path and kept moving. They would walk up to 14 hours a day sometimes only stopping for short breaks. If the family had multiple children it was common to share the duty of mule tending. This allowed the children to switch with each other throughout the day allowing each child a decent break. If you did not have multiple siblings or you were hired to be a mule tender on someone’s boat you more than likely walked 14 hours a day with few breaks. Some mule tenders wore shoes, some did not. They walked in all manners of weather. They would feed their mules using feed sacks as they walked and also during the short breaks the mules and drivers would get as they waited for the boat to go through the lock. The days were long and seemingly endless to the mules and tenders who spent their days walking back and forth along the canals.