Coal

Coal

Coal was the entire reason that the Lehigh and Delaware canals were built. During the War of 1812 Britain blocked our ports which stopped the importation of bituminous coal from Great Britain. This caused us to have to find a domestic source of coal which was found in the Pocono Mountains. This coal was called anthracite coal. It was better than bituminous coal because it was cleaner and burned brighter, hotter and longer. Once these reserves were discovered we needed to figure out how to get it from the mountains near Mauch Chunk to the big cities of Philadelphia and New York. Hence, the birth of the canal system that crisscrossed Pennsylvania.

Coal is a fossil fuel created from the remains of plants that lived and died about 100 to 400 million years ago when parts of the earth were covered with huge swampy forests. Coal is classified as a nonrenewable energy source because it takes millions of years to form. The energy we get from coal today comes from the energy that plants absorbed from the sun millions of years ago.

All living plants store energy from the sun through a process known as photosynthesis. After the plants die, this energy is released as the plants decay. Under conditions favorable to coal formation, however, the decay process is interrupted, preventing the further release of the stored solar energy. Millions of years ago, dead plant matter fell into the swampy water and over the years, a thick layer of dead plants lay decaying at the bottom of the swamps. Over time, the surface and climate of the earth changed, and more water and dirt washed in, halting the decay process. The weight of the top layers of water and dirt packed down the lower layers of plant matter. Under heat and pressure, this plant matter underwent chemical and physical changes, pushing out oxygen and leaving rich hydrocarbon deposits. What once had been plants gradually turned into coal.

Switchback Railroad

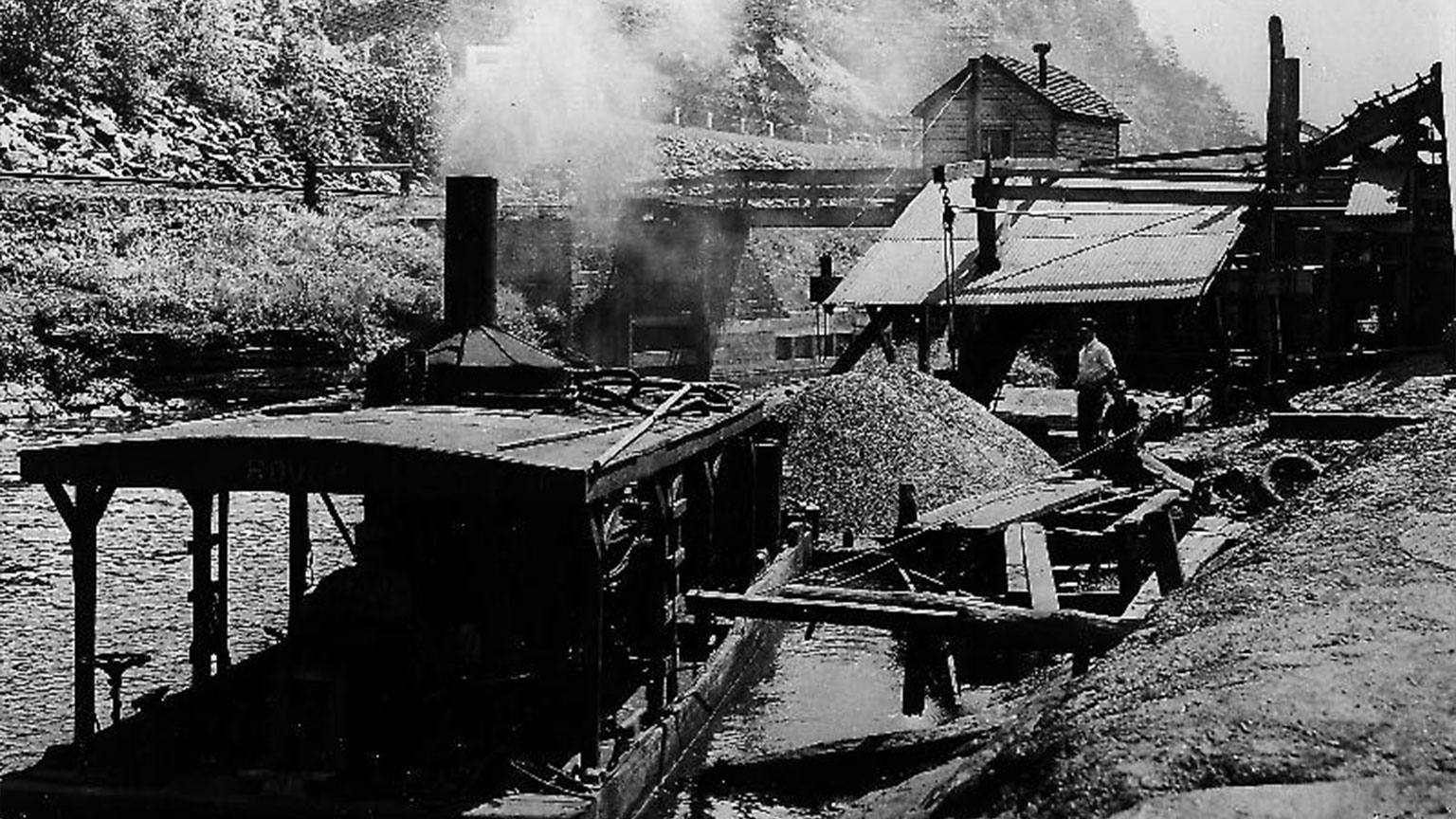

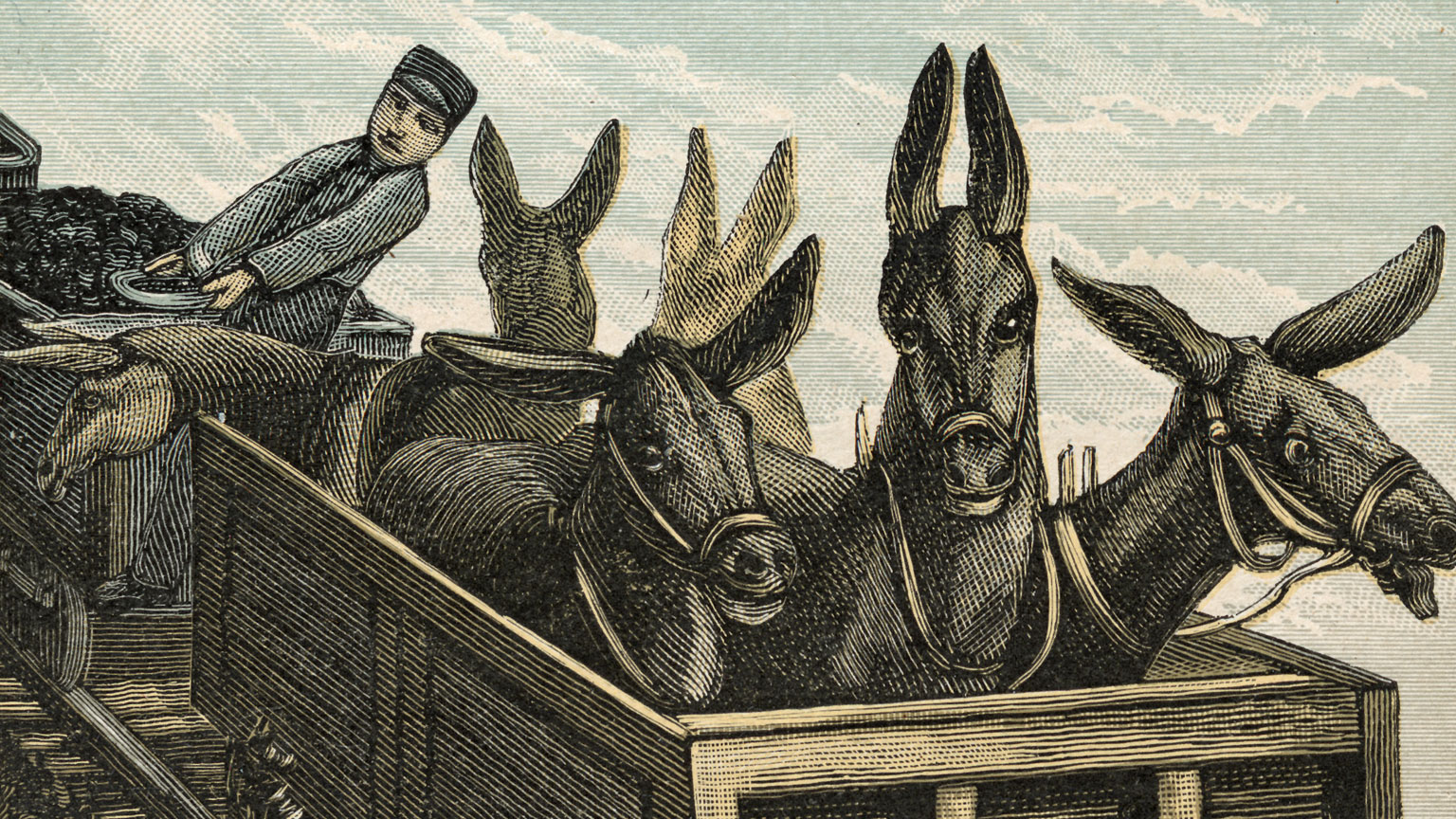

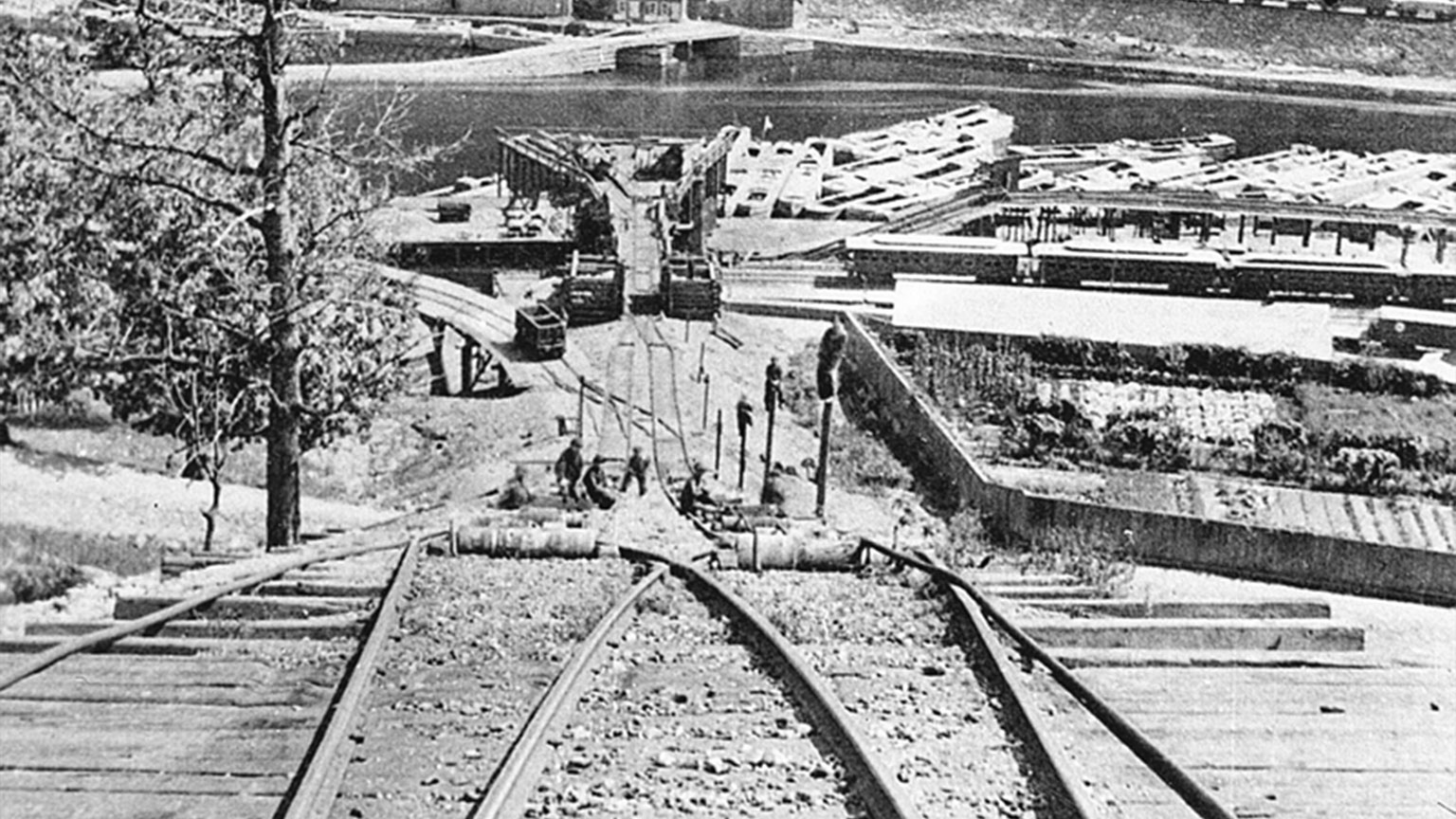

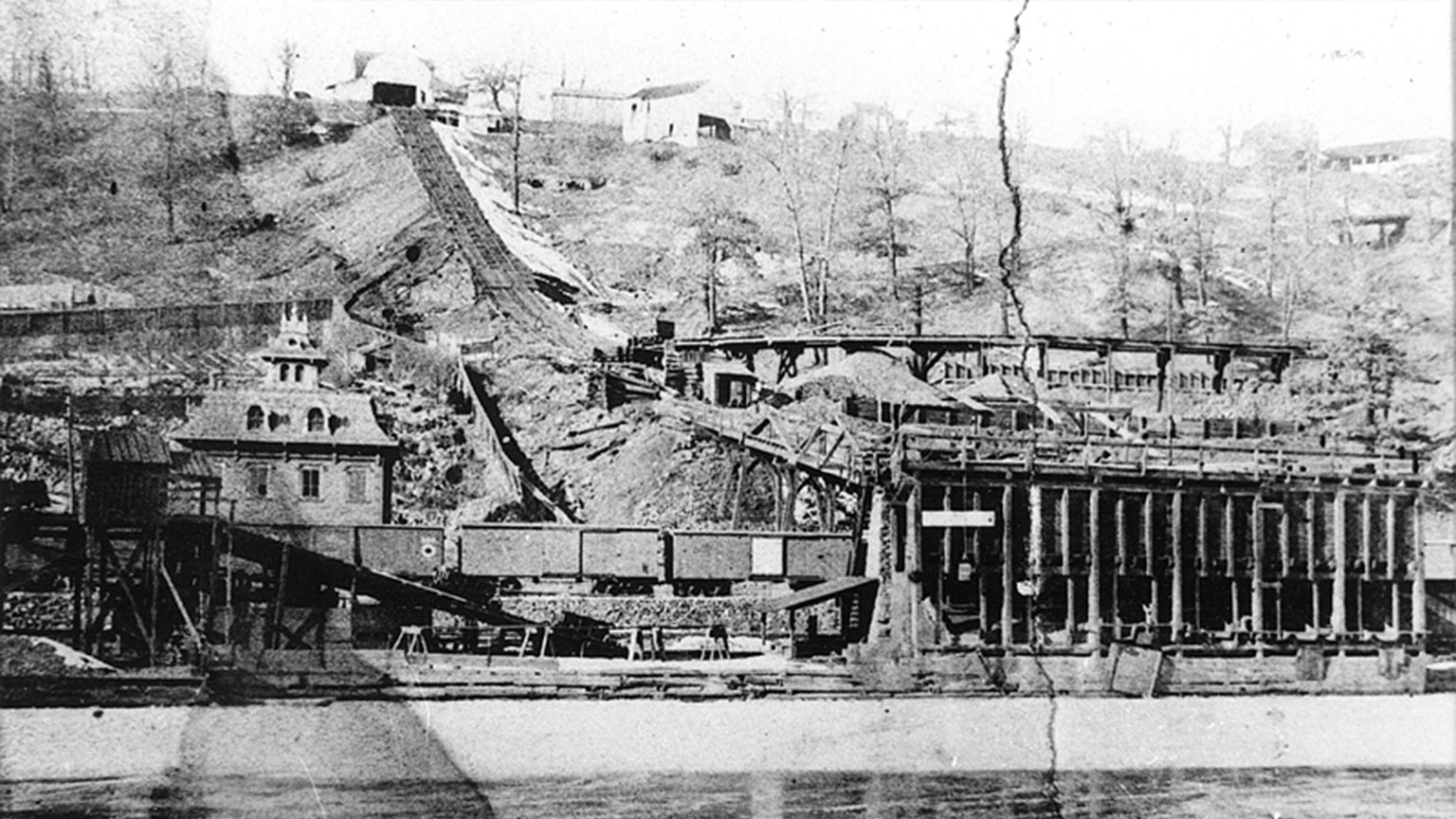

The first railroad in Pennsylvania, and only the second in the whole country, was built in 1828. Its sole job was to move coal from the Summit Coal Mine, located near the town of Mauch Chunk, to the Lehigh River where it could then be transported to the places that needed it. Originally named The Gravity Railroad, it used gravity to propel coal-laden railroad cars down the 5 miles of track to the Lehigh River. It then used mules to pull the cars back up the tracks. In 1846 steam-powered engines were introduced which would eventually replace the mules. Surely, the spectacle of a railroad car full of mules rushing down the railroad tracks to the Lehigh River where they would be hooked back up to empty coal cars in order to pull them back up the mountain was sorely missed.

This system continued moving coal until 1872 when other railroad systems came far enough along to take over the need for the Switchback. This was not the end of the Switchback railroad, however. The railroad continued to make money as a tourist attraction. People paid to ride the Switchback, which was the inspiration for the invention of the roller coaster. Although it no longer exists, during its heyday it was a marvel to behold. A ride on the switchback was something anyone would remember.

A Ride on the Switchback - Late 19th century visitors to Mauch Chunk frequently arrived by train, approaching the town from the Narrows, a gorge that strongly suggests the area's pseudonym, "The Switzerland of America."

O.S. Senter wrote in 1873, "Here we have at a single glance a view of the town, the coal shoots, the 'Switchback", the winding bounding river, with its locks, falls and rapids, and above all the grand old mountain summits, which rise up skyward, and towering towards the vast blue vault of the heavens, seem to rest against and support its mighty dome like the pillars of time; and as the wind and storm sweep across the topmost peaks, their trees wave among the clouds like the dark locks of giant forms. Away up yonder sits Pisgah, in majestic simplicity, like a monarch enthroned, ruling among his fellows with power and might supreme."

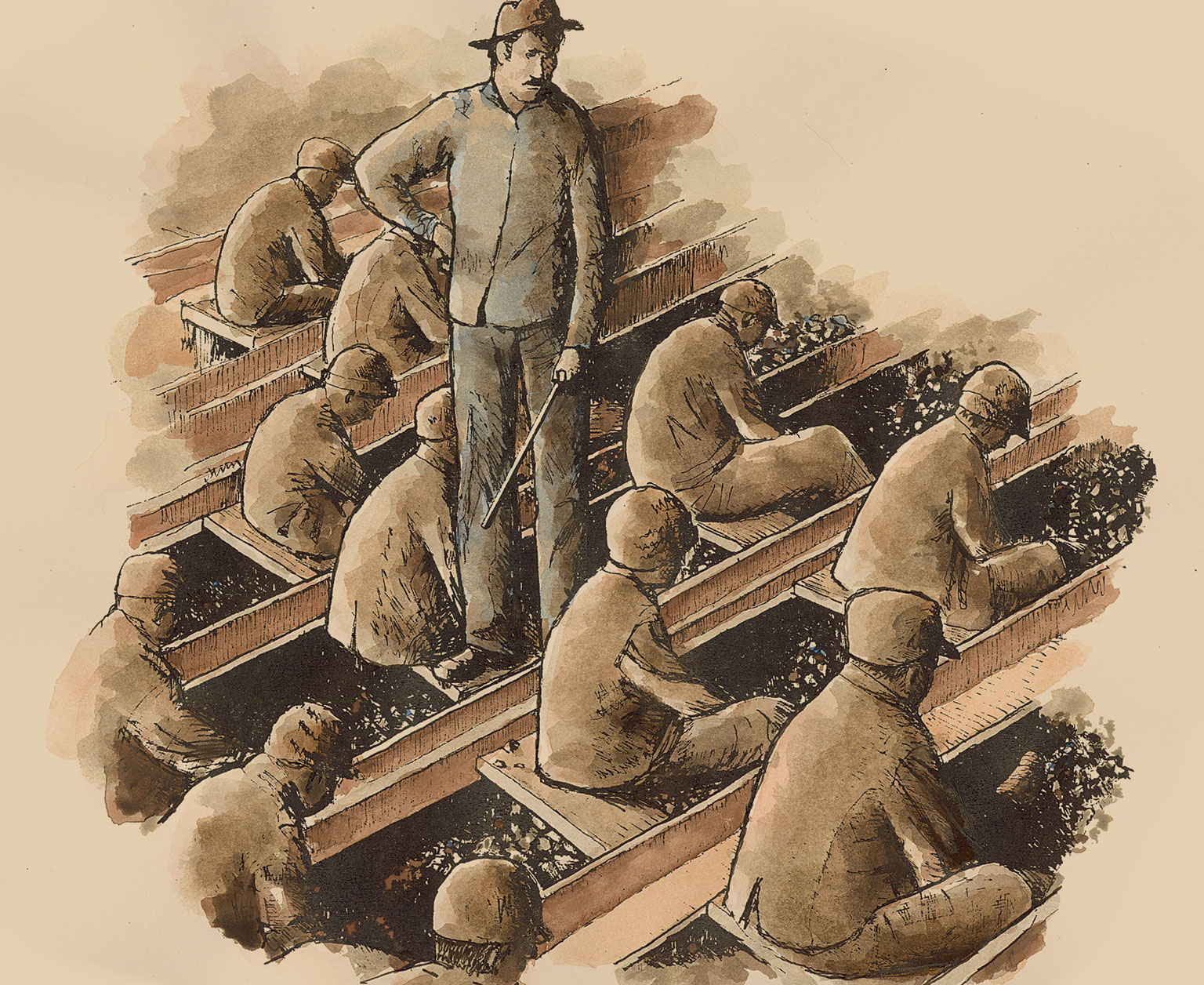

Breaker Boys

Breaker boys worked in buildings called “crushers” where huge rollers broke the coal into smaller chunks for shipping. The job of the breaker boy was to separate the coal that came down the chute from other rocks and impurities such as slate. Though this was an important job, it was done by the least-skilled and smallest workers. It was a back breaking job that paid very little money, but to coal miners’ families every penny counted, so boys as young as nine or ten were often put to work as breaker boys.

An excerpt from The Bitter Cry of the Children by John Spargo:

Work in the coal breakers is exceedingly hard and dangerous. Crouched over the chutes, the boys sit hour after hour, picking out the pieces of slate and other refuse from the coal as it rushes past to the washers. From the cramped position they have to assume, most of them become more or less deformed and bent backed like old men. When a boy has been working for some time and beins to get round shouldered his fellows say that, "He's got his boy to carry round wherever he goes." The coal is hard, and accidents to the hands, such as cuts, broken, or crushed fingers, are common among the boys. Sometimes there is a worse accident: a terrified shriek is heard, and a boy is mangled and torn in the machinery, or disappears in the chute to be picked out later smothered and dead. Clouds of dust fill the breakers and are inhaled by the boys, laying the foundation for asthma and miners' consumption.

I once stood in a breaker for half an hour and tried to do the work a 12 year old boy was doing day after day, for 10 hours at a stretch, for pennies a day. The gloom of the breaker appalled me. There was a blackness, clouds of deadly dust enfolded everything, the harsh, grinding roar of the machinery and the ceaseless rushing of coal through the chutes. I tried to pick out the pieces of slate from the hurrying stream of coal, often missing them; my hands were bruised and cut in a few minutes; I was covered from head to foot with coal dust, and for many hours afterwards I was expectorating some of the small particles of anthracite I had swallowed.

I could not do that work and live, but there were boys of 10 and 12 years of age doing it. Some of them had never been inside of a school; few of them could read a child's primer. True, some of them attended the night schools, but after working 10 hours in the breaker the educational results from attending school were practically nil. "We goes fer a good time, an' we keeps de guys wot's dere hoppin' all de time," said little Owen Jones, whose work I had been trying to do.

From the breakers the boys graduate to the mine depths, where they become door tenders, switch boys, or mule drivers. Here, far below the surface, work is still more dangerous. At 14 or 15 the boys assume the same risks as the men, and are surrounded by the same perils. Think of what it means to be a trap boy at 10 years of age. It means to sit alone in a dark mine passage hour after hour, with no human soul near; to see no living creature except the mules as they pass with their loads, or a rat or two seeking to share one's meal; to stand in water or mud that cover the ankles, chilled to the marrow by the cold draughts that rush in when you open the trap door for the mules to pass through; to work for 14 hours - waiting- opening and shutting a door - then waiting again for their few cents; to reach the surface when all is wrapped in the mantle of night and to fall to the earth exhausted and have to be carried away to the nearest shack to be revived before it is possible to walk to the farther shack called "home".

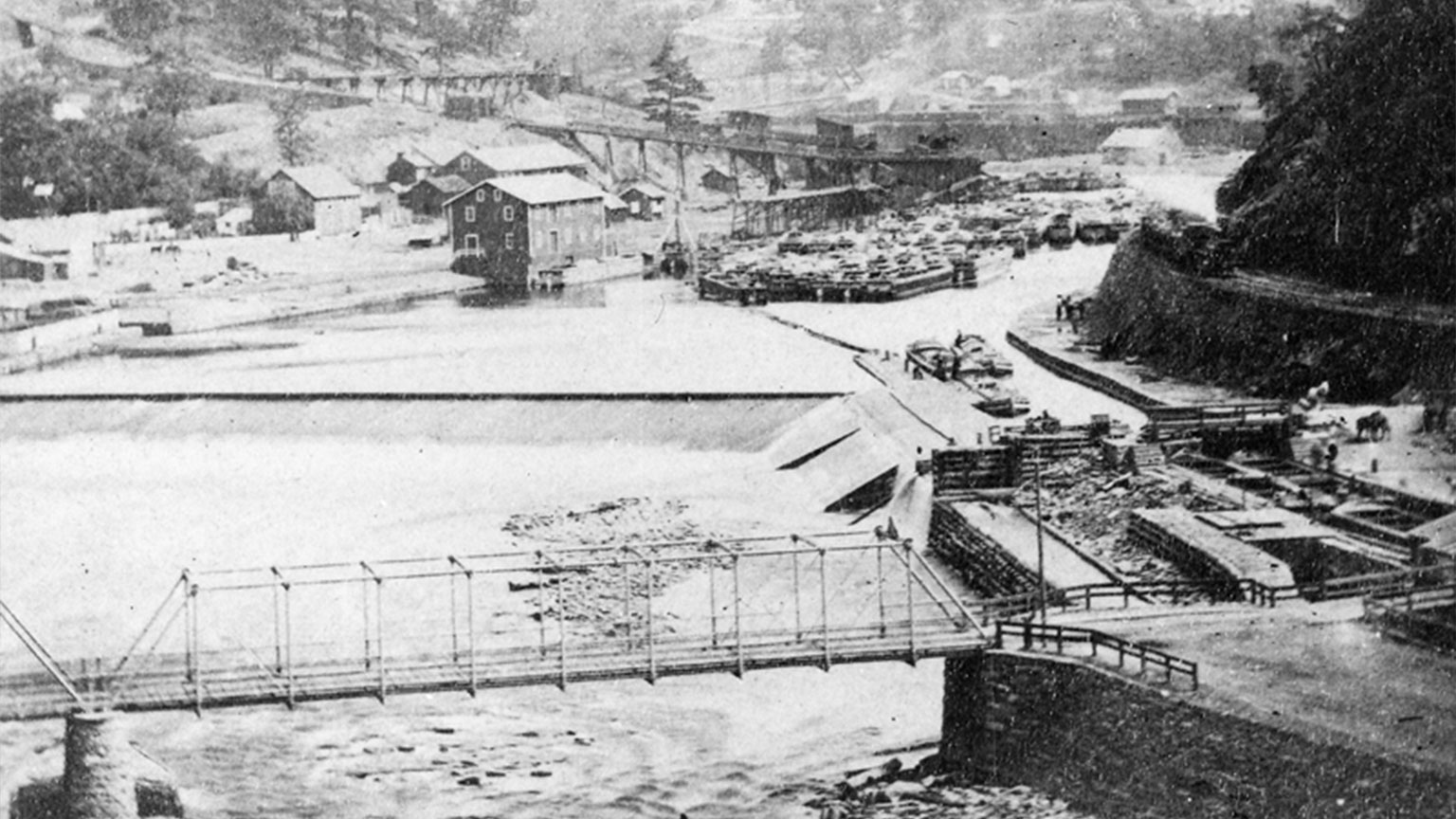

Lockport

Lockport was a small but thriving village located in southwest Lehigh Township along the Lehigh River, approximately two miles south of Walnutport. The village was situated at the mouth of Bertsch Creek, which took its name from David Bertsch, a settler who came to the area in 1762.

Lockport was an important boat building and repair center on the Lehigh Canal from the mid- to late 1800s. Workers built, repaired and painted canal boats and also fixed leaks with hot tar. The center was owned by Thomas Beck, who also owned Beck’s Tavern, also called the Lockport Hotel. The hotel housed travelers along the canal as well as boatmen who were seeking a night of sleep outside their boat cabins. In 1874, Lockport had 10 dwellings and a one-room schoolhouse. In 1967, the Lockport Hotel was destroyed by fire.

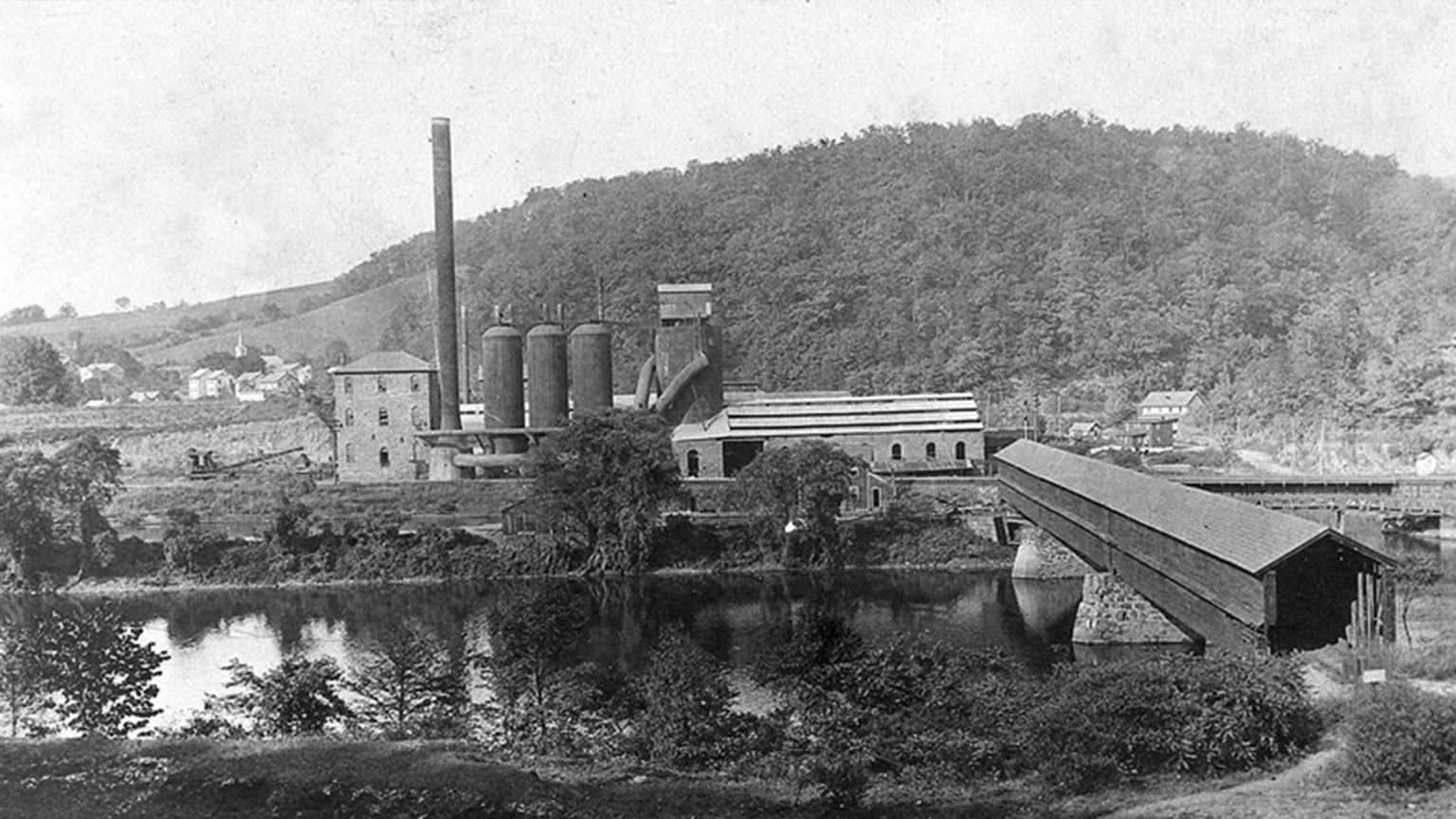

Iron Pigs

Pig Iron is the intermediate product of smelting iron ore with coke (coal burned to a different form at high temperatures), usually with limestone as a flux. Pig iron has a very high carbon content, which makes it very brittle and not useful directly as a material except for limited applications. The traditional shape of the molds used to make ingots was a branching structure formed in sand, with many individual ingots at right angles to a central channel or runner. Such a configuration is similar in appearance to a litter of piglets suckling on a sow. When the metal had cooled and hardened, the smaller ingots (the pigs) were simply broken from the much thinner runner (the sow), hence the name pig iron, or iron pigs. As pig iron is intended for remelting, the uneven size of the ingots and inclusion of small amounts of sand was insignificant compared to the ease of casting and of handling.