Lumber Industry

Lumber Industry

Timber is one of Pennsylvania's greatest natural resources. When William Penn arrived in 1682, it is estimated that 90% of the over 20 million acres now comprising the Commonwealth, were covered with dense stands of white pine, eastern hemlock and mixed hardwoods. Forests near the first settlements were cleared immediately to provide farming fields and to supply construction materials. Gradually, as agriculture and industry developed, the demand for wood products increased.

By the eve of the Revolution, lumbering had spread into the interior of the Commonwealth. The Delaware, lower Susquehanna, and Schuylkill rivers were filled with rafts of lumber and logs, and the banks of creeks and rivers of Western Pennsylvania were dotted with mills. While sawing lumber and building boats and ships represented the principal use of wood in Pennsylvania's pioneering economy, the forest also furnished fuel, potash, tanbark, wood for furniture and coopering, rifle stocks, shingles, household utensils, charcoal - to name only a few of the many uses. The export of lumber and its by-products was a worthwhile enterprise wherever it was possible to reach the ports of Philadelphia and Baltimore.

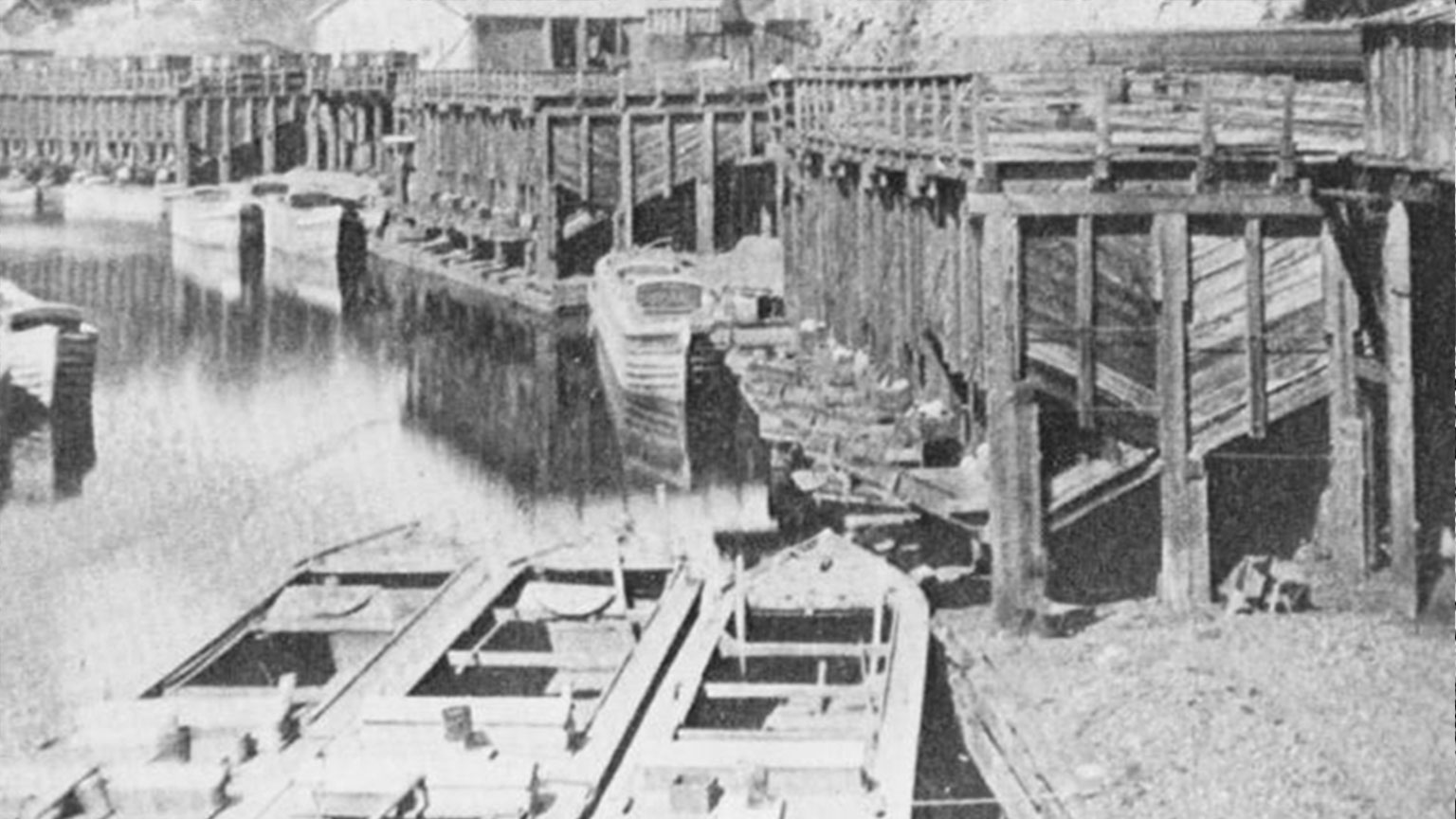

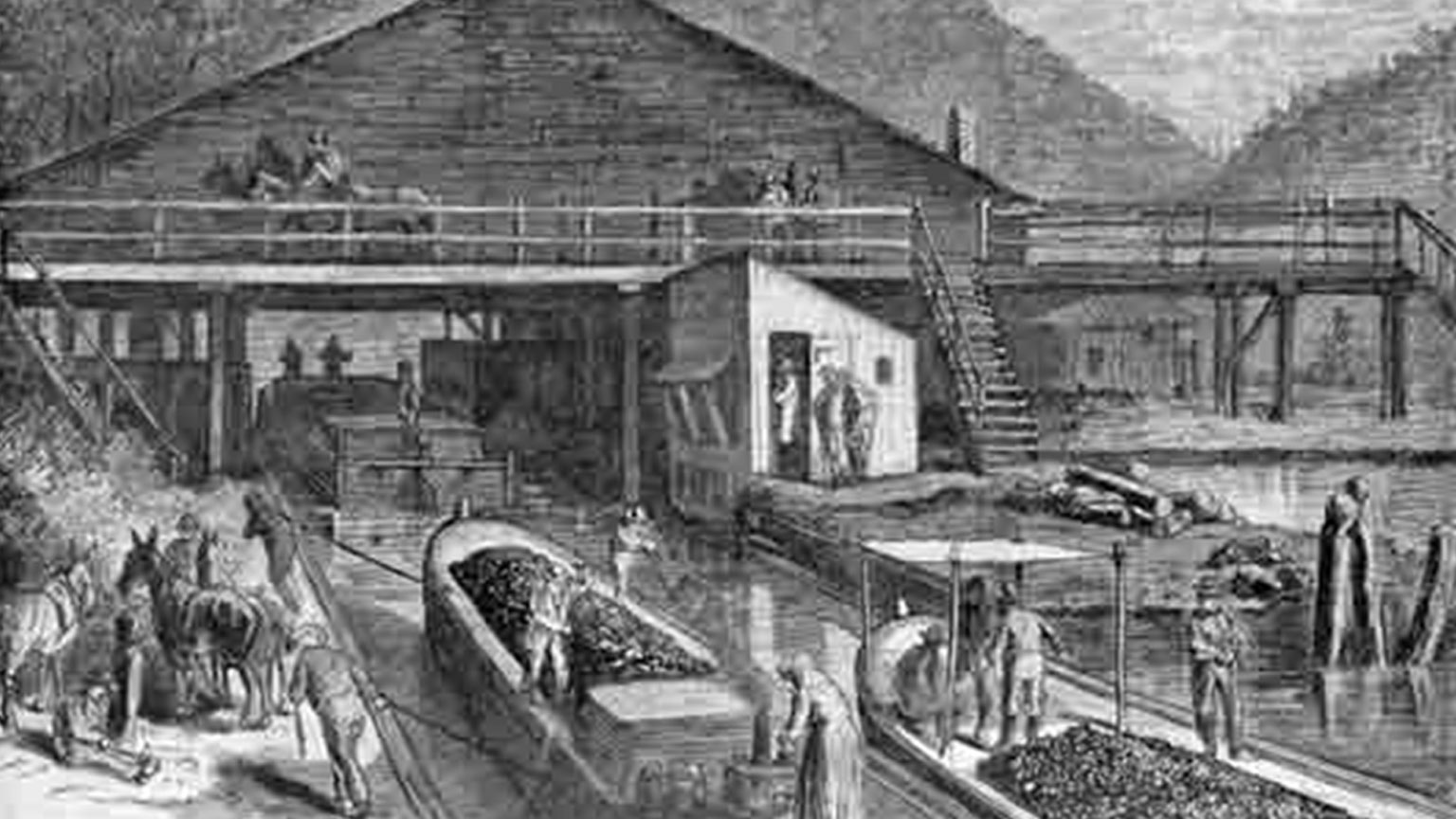

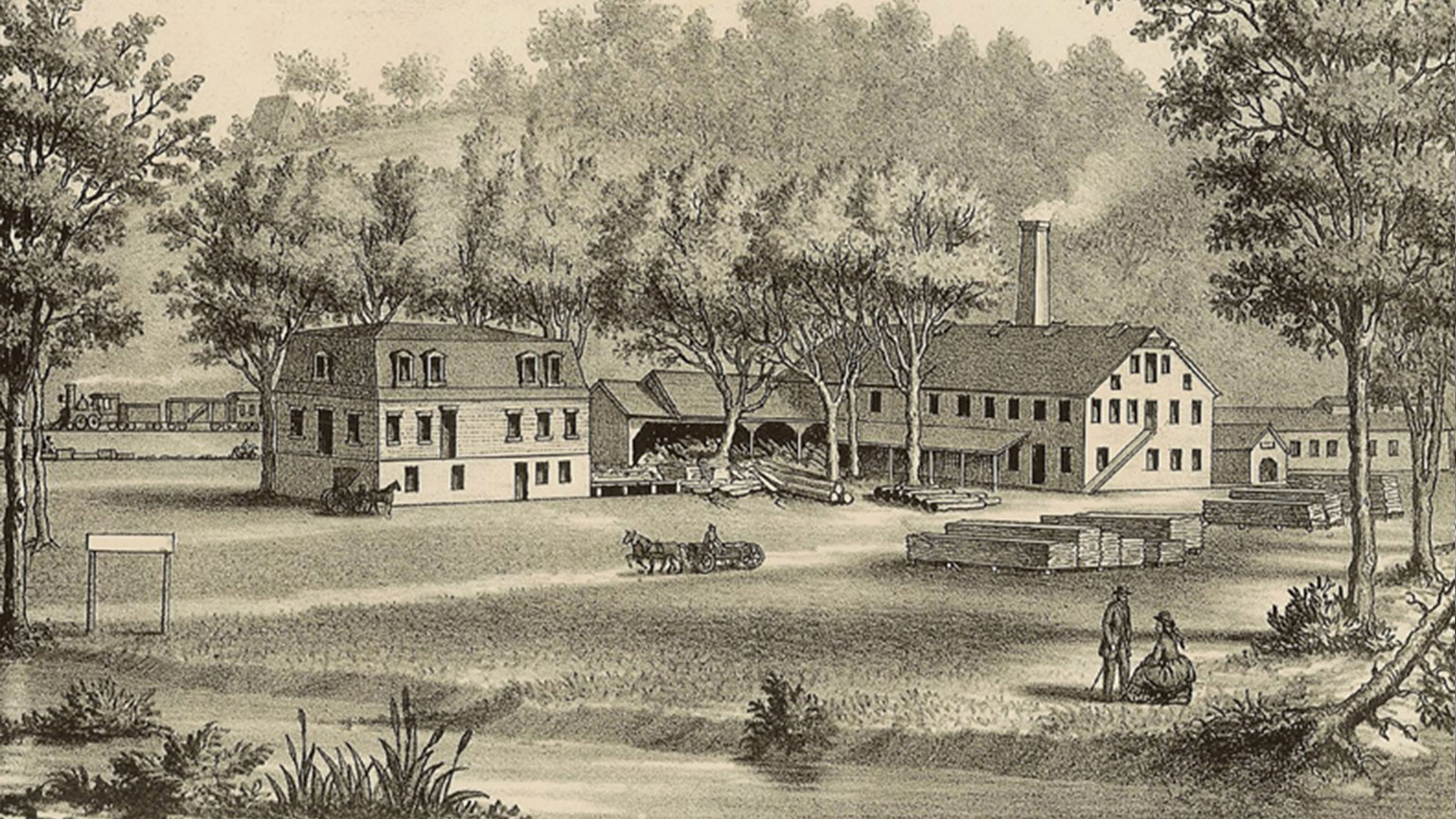

After 1850, the rise of the lumber business was rapid and was given further impetus by the demand for lumber produced both by the Civil War and the growth of the country. The introduction of steam driven machinery, combined with the use of the circular saw blade revolutionized sawmilling. During the period between 1850 and 1870, the center of the lumber industry shifted into northern and central Pennsylvania. Williamsport, with 29 sawmills, became known as the lumber capital of the world. Its great mills, strategically located on the Susquehanna River, were supplied by logs floated down river from tributary streams to the north. The log boom, operated by the Susquehanna Boom Co., stretched seven miles along Williamsport's river front and was credited with a holding capacity of over 250 million board feet of lumber. It is within this period that Pennsylvania was the greatest producing state in the nation.

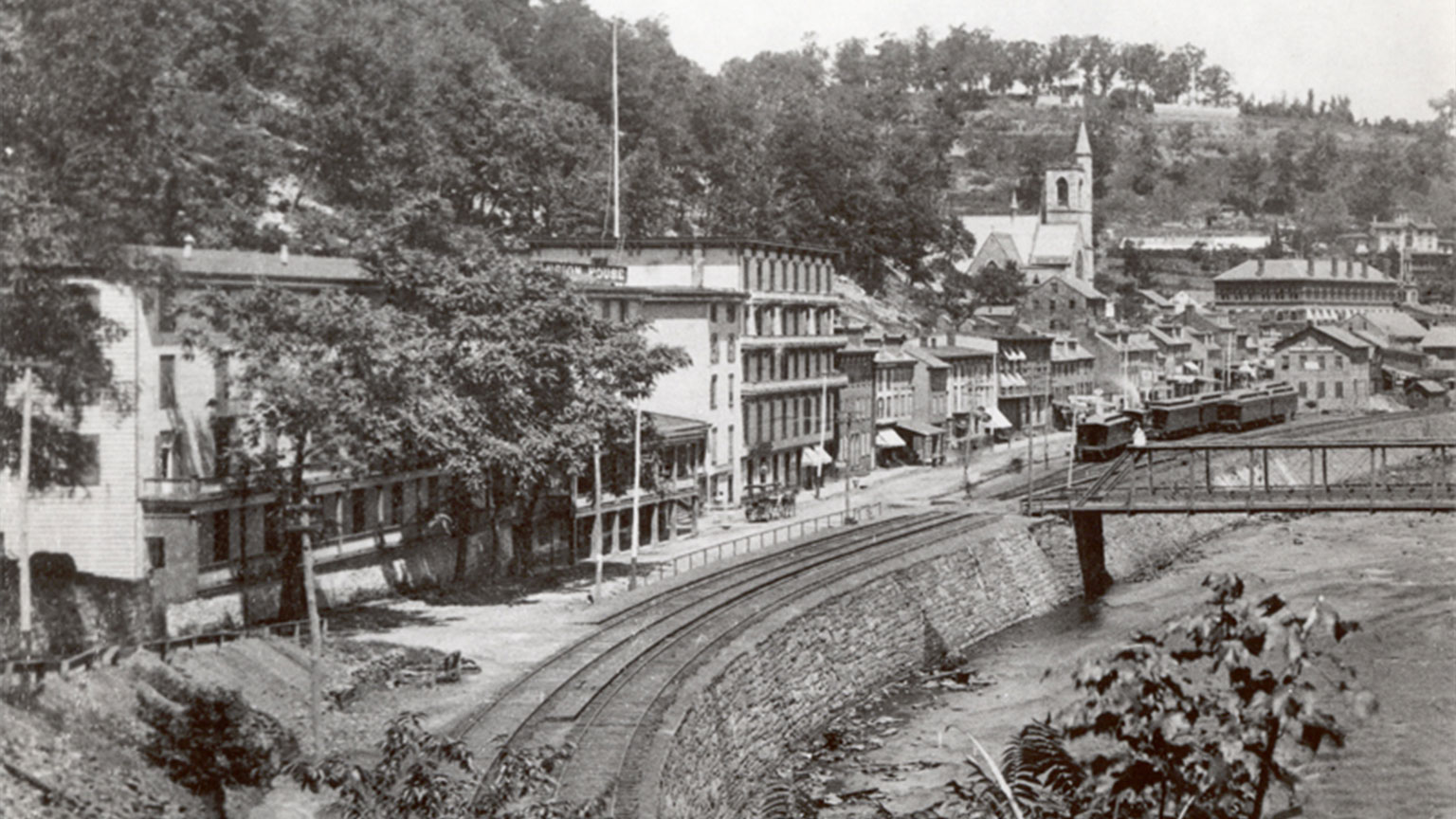

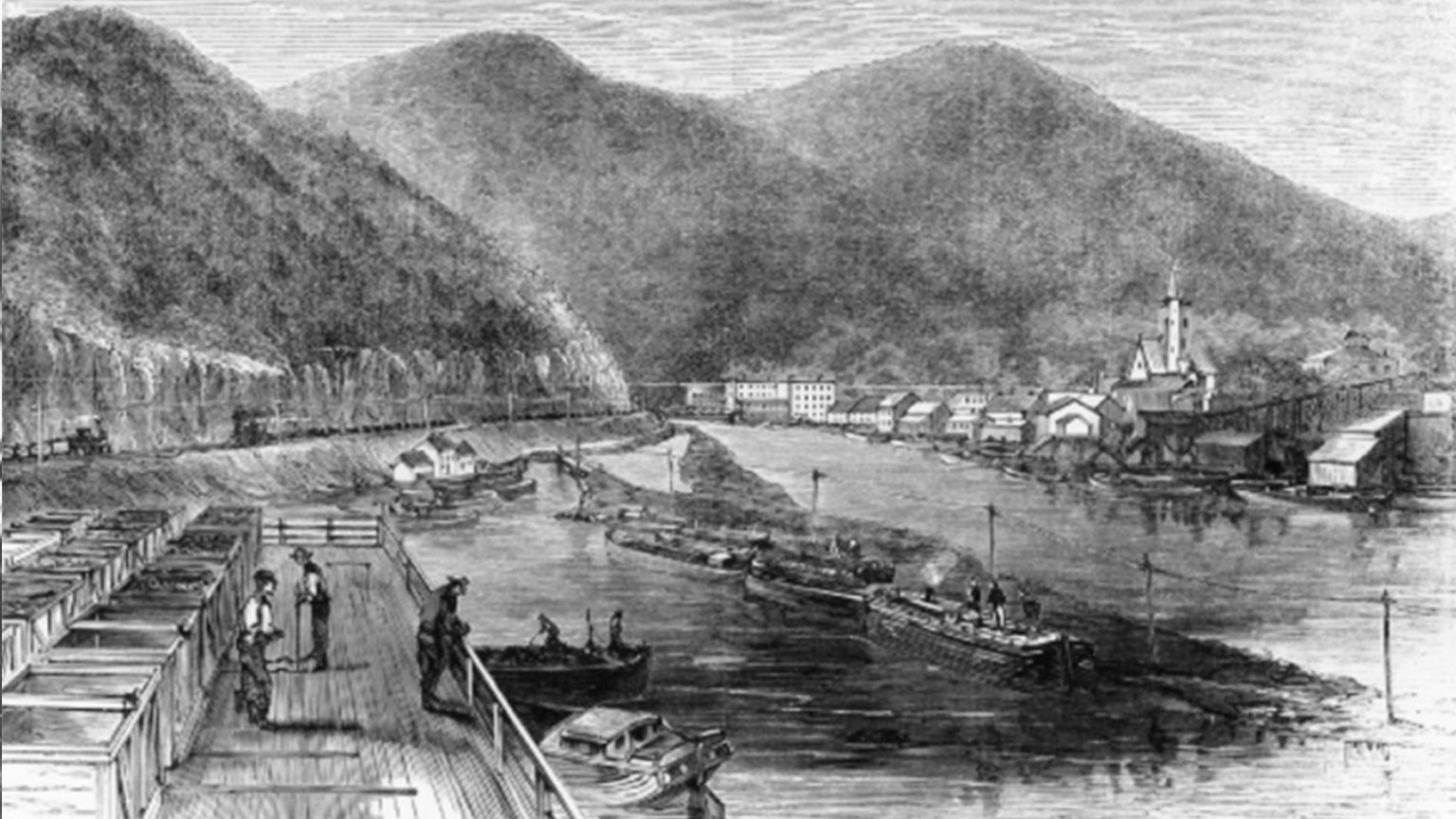

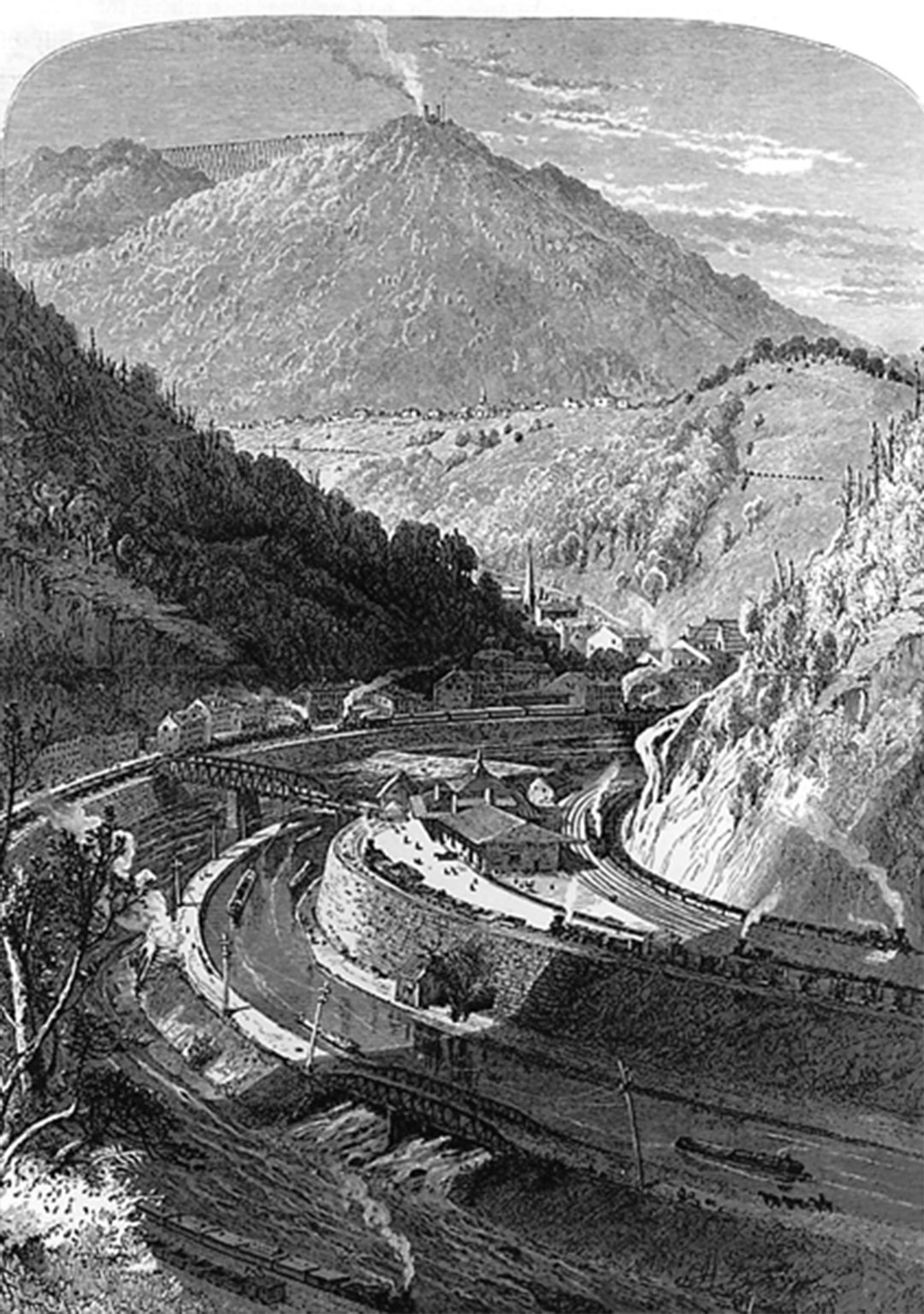

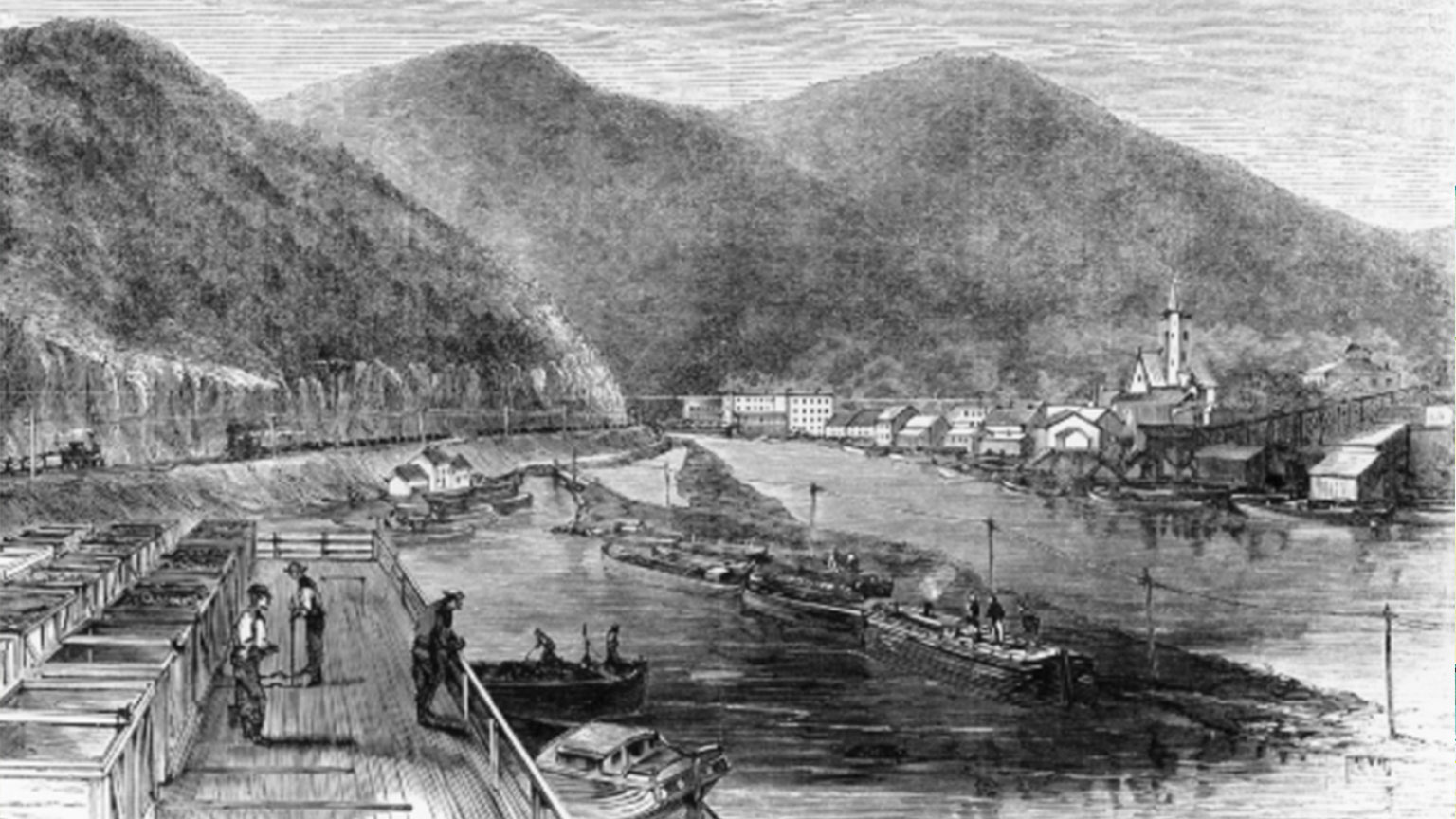

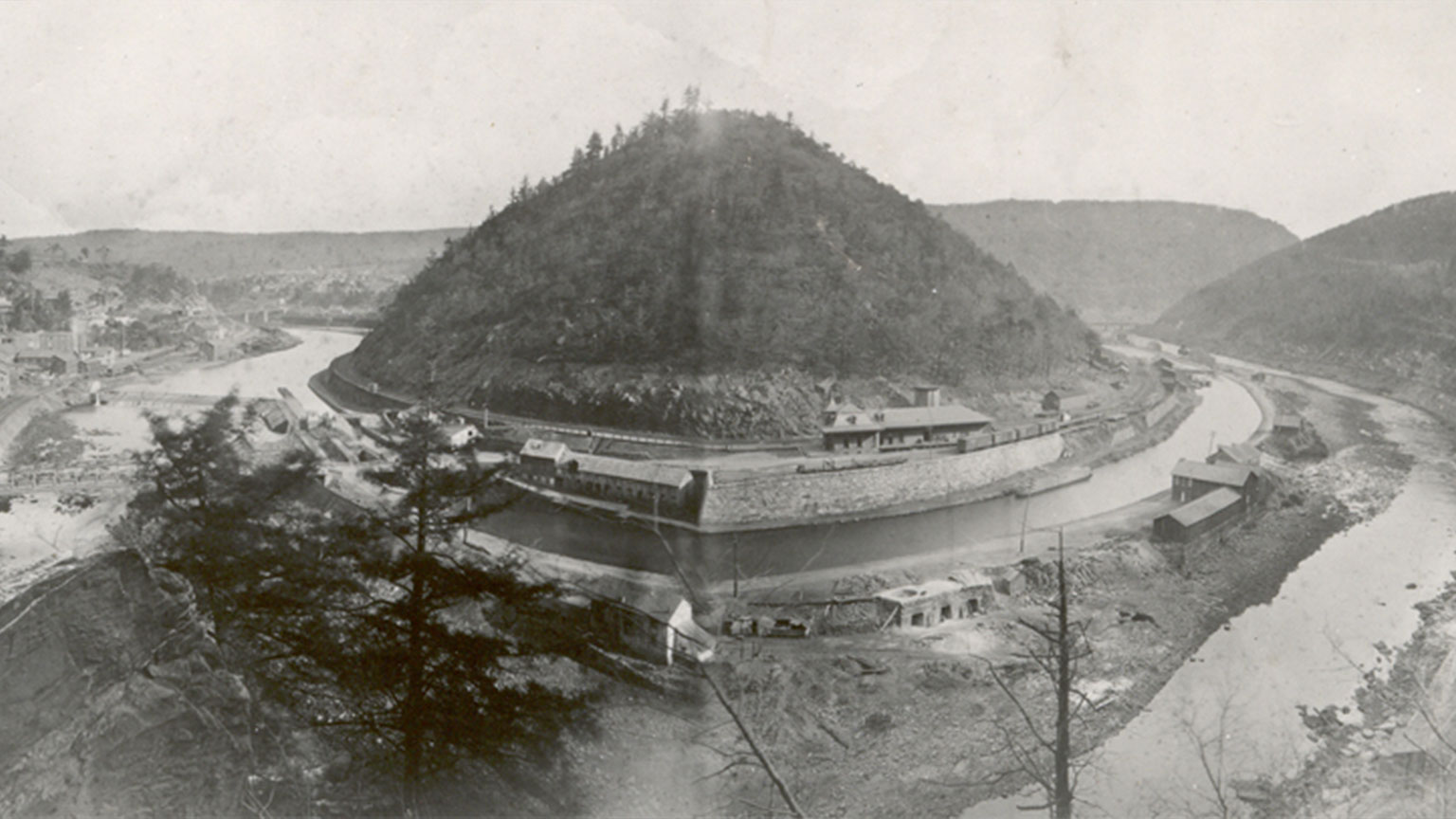

Mauch Chunk

Mauch Chunk, now known as Jim Thorpe, is situated on the west bank of the Lehigh River in Carbon County, approximately four miles north of Lehighton. The name Mauch (pronounced mock) Chunk was derived from the term “bear mountain” in the language of the native Lenni Lenape people. The name is a reference to the round mountain on the east side of the Lehigh River that resembles a sleeping bear. Learn more about Mauch Chunk.

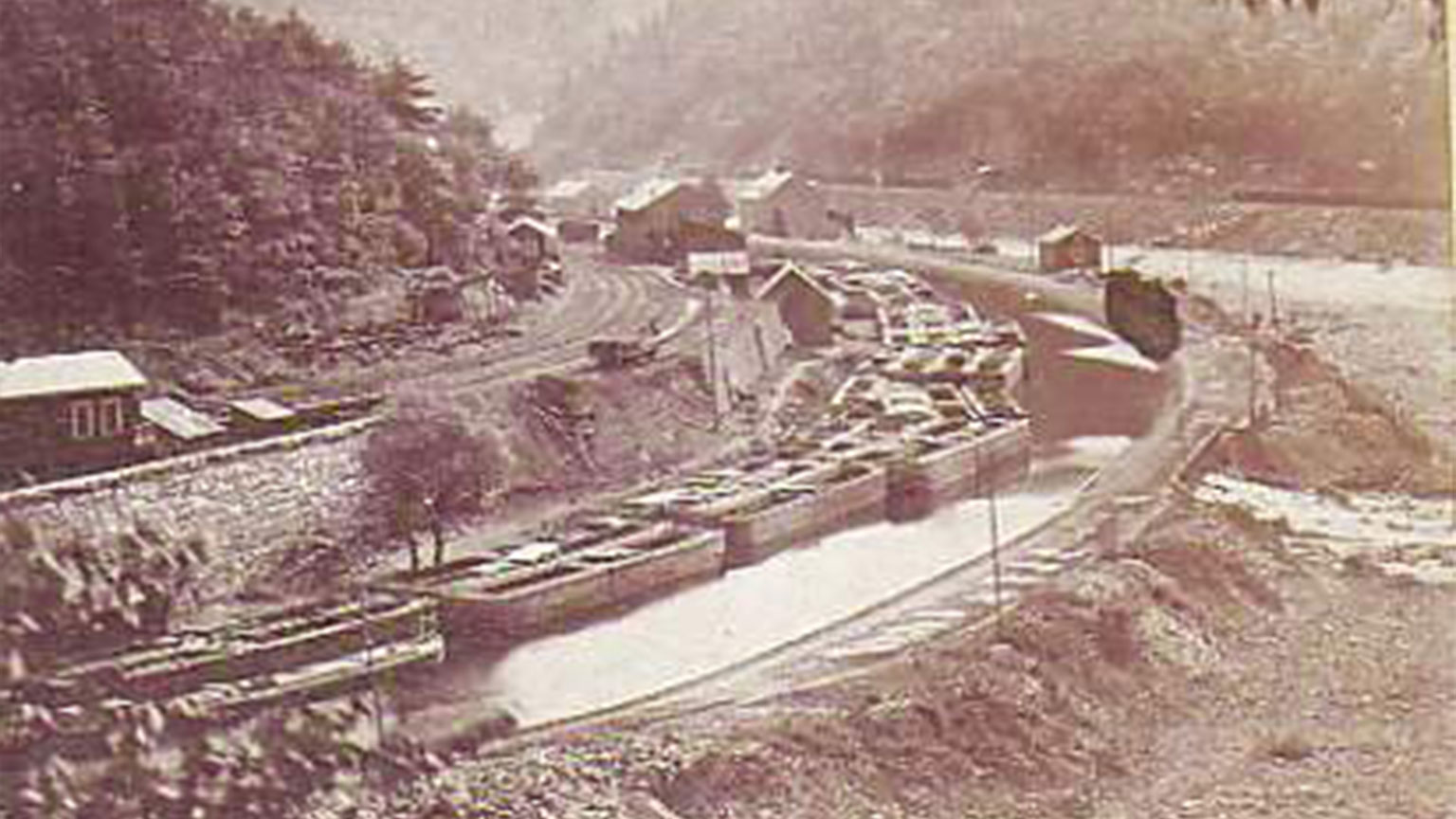

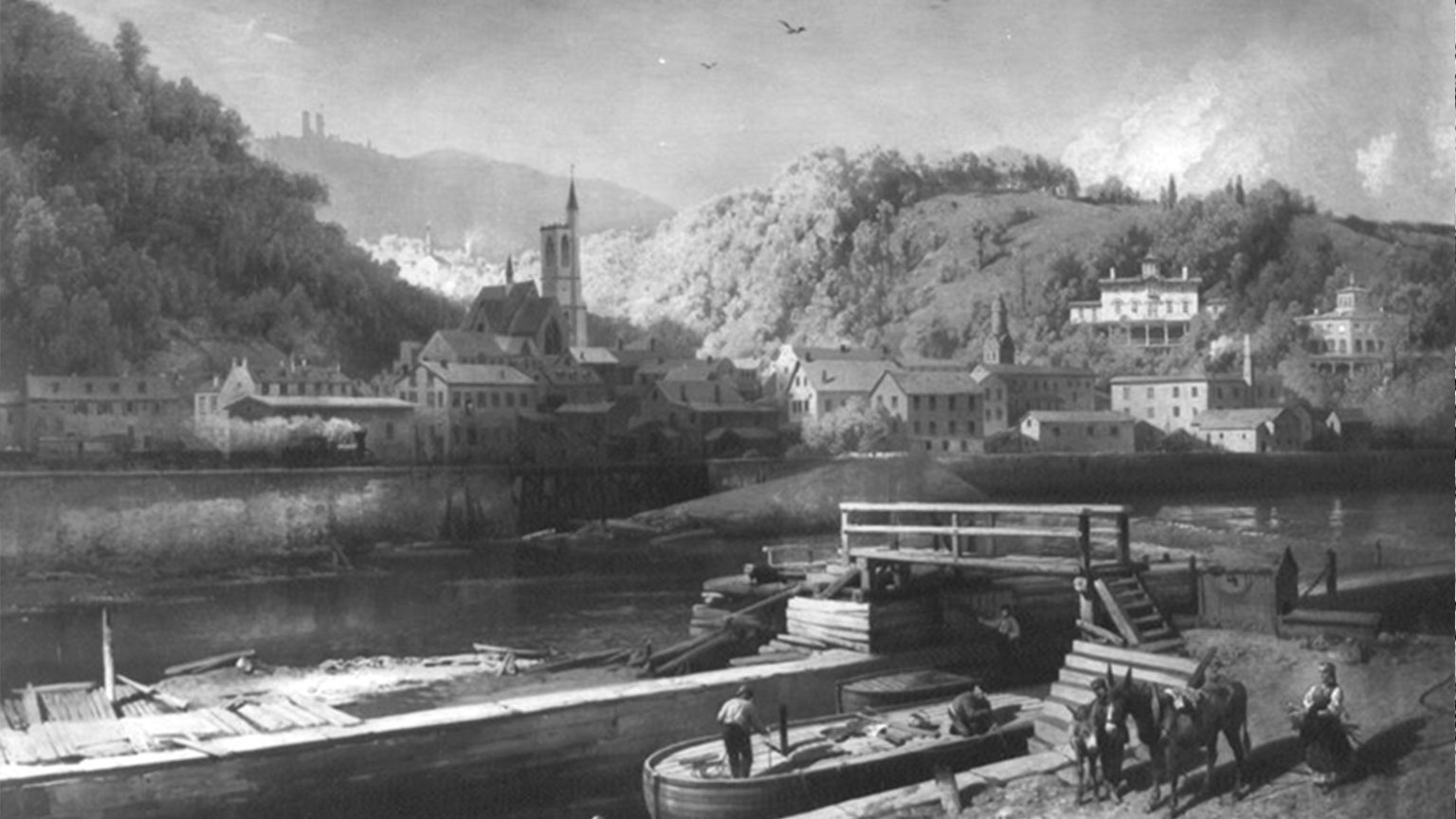

White Haven

John Lines became the first settler of the area when he brought his family on sled from Hanover Township just south of Wilkes-Barre in April 1824. The one-home settlement was called Linesville for many years until it was officially incorporated as White Haven in 1843. Learn more about White Haven.

Lumber Camp

A typical lumber camp was an isolated forest community, as comfortless as it was isolated. This was the area the lumberjacks would call home while they spent their days cutting down trees in the surrounding forest. The camp always had a bunkhouse and a mess hall, made of logs or planks and rough boards. These were either separate structures or part of one large building. Sleeping bunks were wooden shelves built one above each other. The loggers slept on straw mattresses called "ticks." The mess hall contained a long plank table and plank seats. The kitchen might be at the end of the mess hall or it could be a separate, adjoining building.

A cook and a "cookee" prepared the food. They were often two men, but could be a man and his wife. The food was wholesome and the men consumed enormous quantities of it. Salted meat was a mainstay of a lumber camp diet, although fresh meat was used when it could be obtained from the forest or a nearby farm. Other common food items were bread, butter, corn bread, crackers, potatoes etc. Some accommodations were made for a gathering place, where a pot bellied stove kept the room piping hot. Sometimes the men would dance to the music of a fiddle. But normally, lumberjacks were too tired to stay up long. They retired early and woke before daylight in order to be in the forest just after dawn.

In addition to the bunkhouse and mess hall, the camp included a stable, a storehouse where men would buy necessary items, and a blacksmith shop where horses were shod, chains mended, canthooks sharpened and sled runners repaired. The camp was not for families. Lumberjacks would return home to their families when they were done with the season of lumberjacking.

Clearcutting Land

The lumber industry's practice of clearcutting coniferous and deciduous forests in the 19th century had dire consequences for other forest life. Once trees were cut, animals lost their homes, or habitat. Birds, rodents and other animals in the forest food web were affected. Most species' populations suffered dramatically. The rich soil of the forest floor, which had been shaded for centuries, now was exposed to the drying effects of the sun and the erosional effects of rain and wind. Topsoil was washed away and other plants (producers) in the food web disappeared. Eroded soil wound up in nearby streams where it settled on the bottom and negatively affected aquatic life. The loss of the spongelike forest humus also led to severe runoff during rainstorms and subsequent flooding.

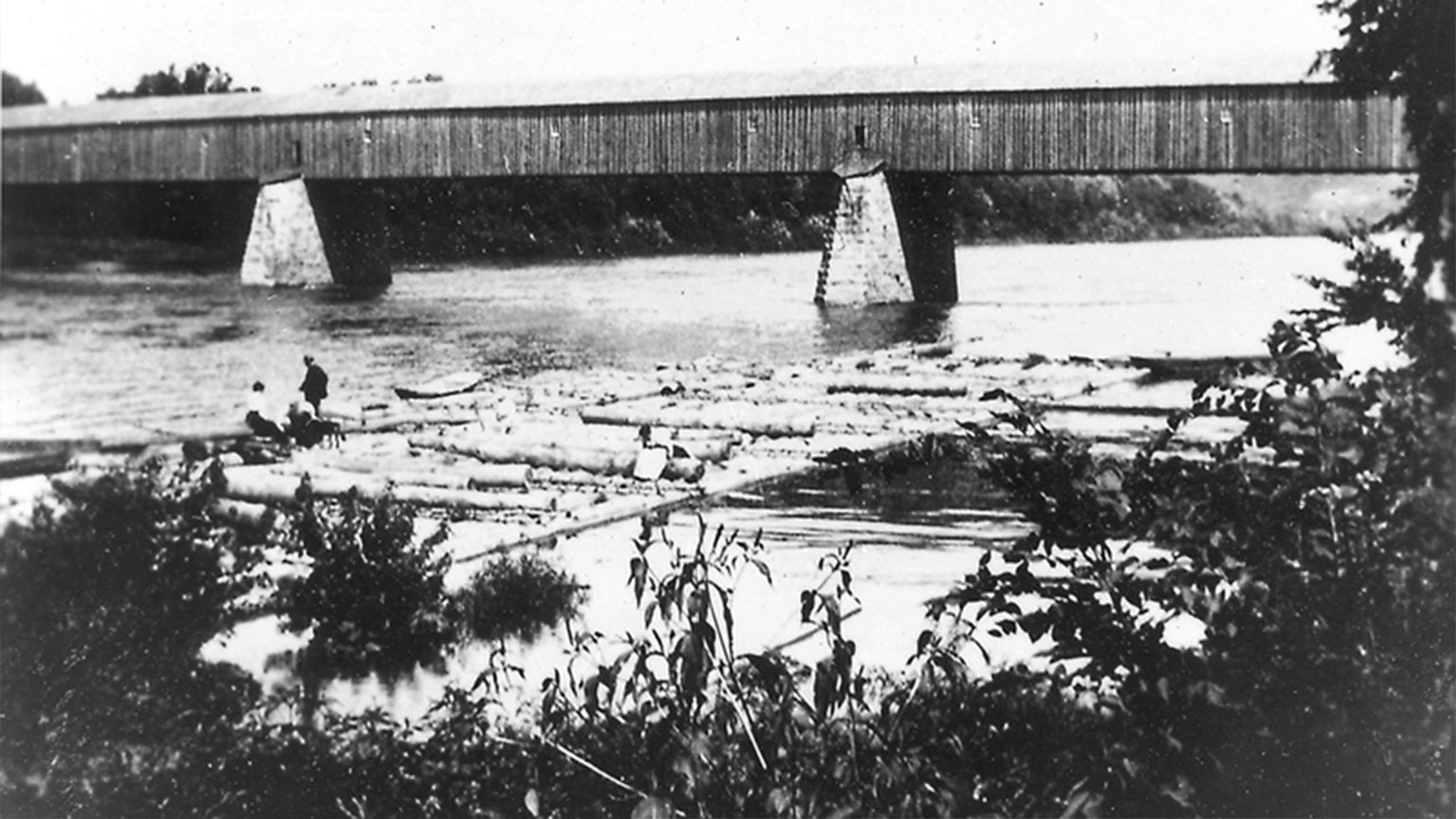

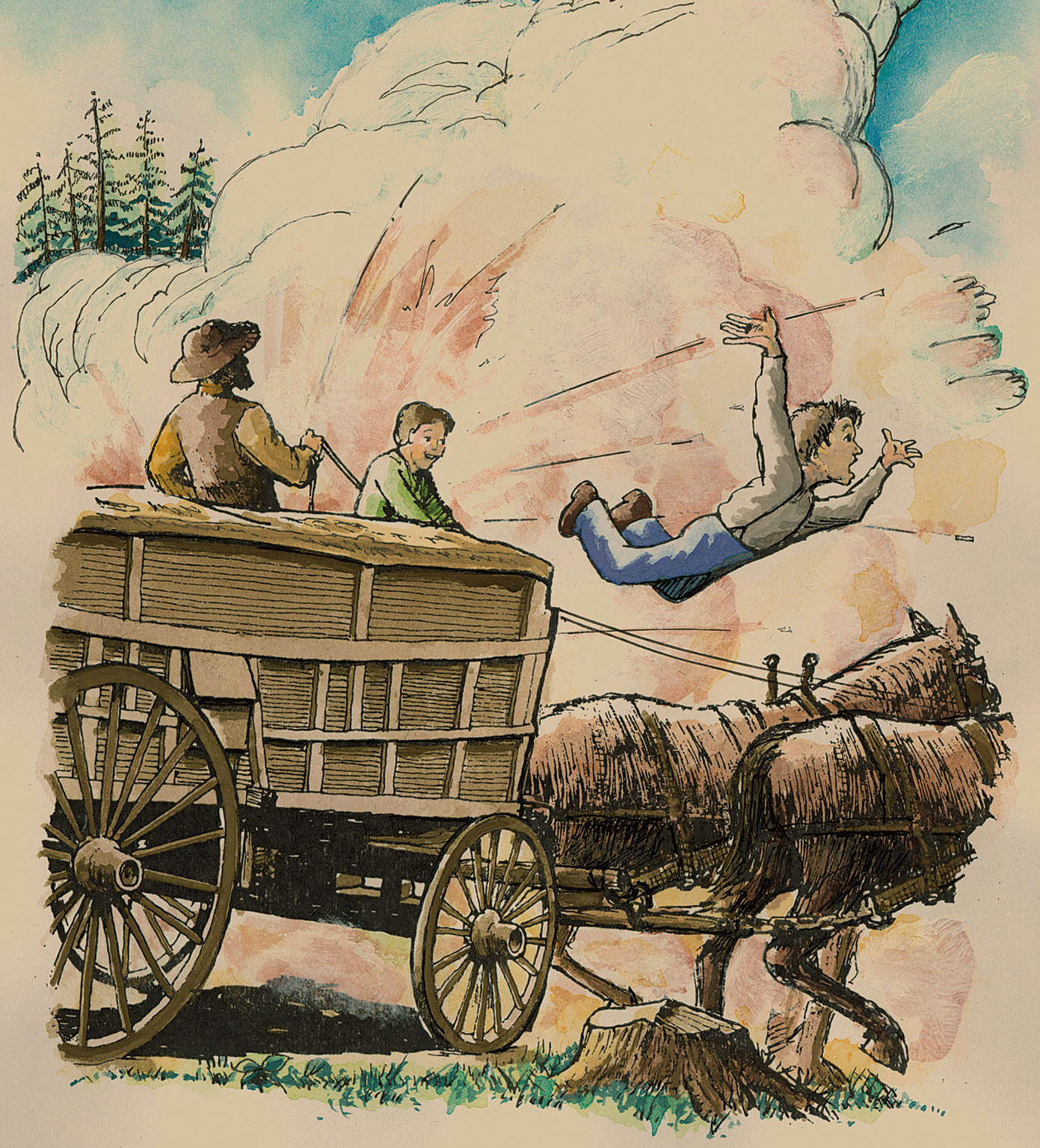

Houses, Bridges, Carts, Boats & More

At a time when building materials had to come from nature, wood was a great commodity. It was used to build things such as houses, bridges, carts and boats. It was also used to heat homes. Lumber was a great source of income for many people, from the men who worked in the lumber camps to the industry that shipped the wood to the men who bought the wood to turn into furniture or buildings. People noticed the forests disappearing around them, but for the most part they looked at this as progress. Land was being cleared to make room for things such as farms and communities. It would be some time before people started to worry for the environment.

Lehigh River Runs Black

The Lehigh Gorge was once lush with white pines and hemlock trees. These forests were clear cut for their wood, but also the tannin in the hemlock which was used to tan leather. The Lehigh Tannery, built in the mid 1850s, used the tannin to tan hides. The denuded forests eroded and the tannin from the discharge of the tanning tanks as well as the fallen hemlocks turned the Lehigh River black. Lehigh Tannery became the second largest tannery in the United States by 1860. By 1875 most of the saleable timber had been clear-cut, with thousands of acres of dried treetops and other wooden debris left on the ground. That same year a spark from a passing coal- fired steam locomotive ignited a massive forest fire that burned the debris, the remaining standing timber, the sawmills, and their lumber stockpiles. This forest fire ended the lumber era in the Lehigh Gorge.

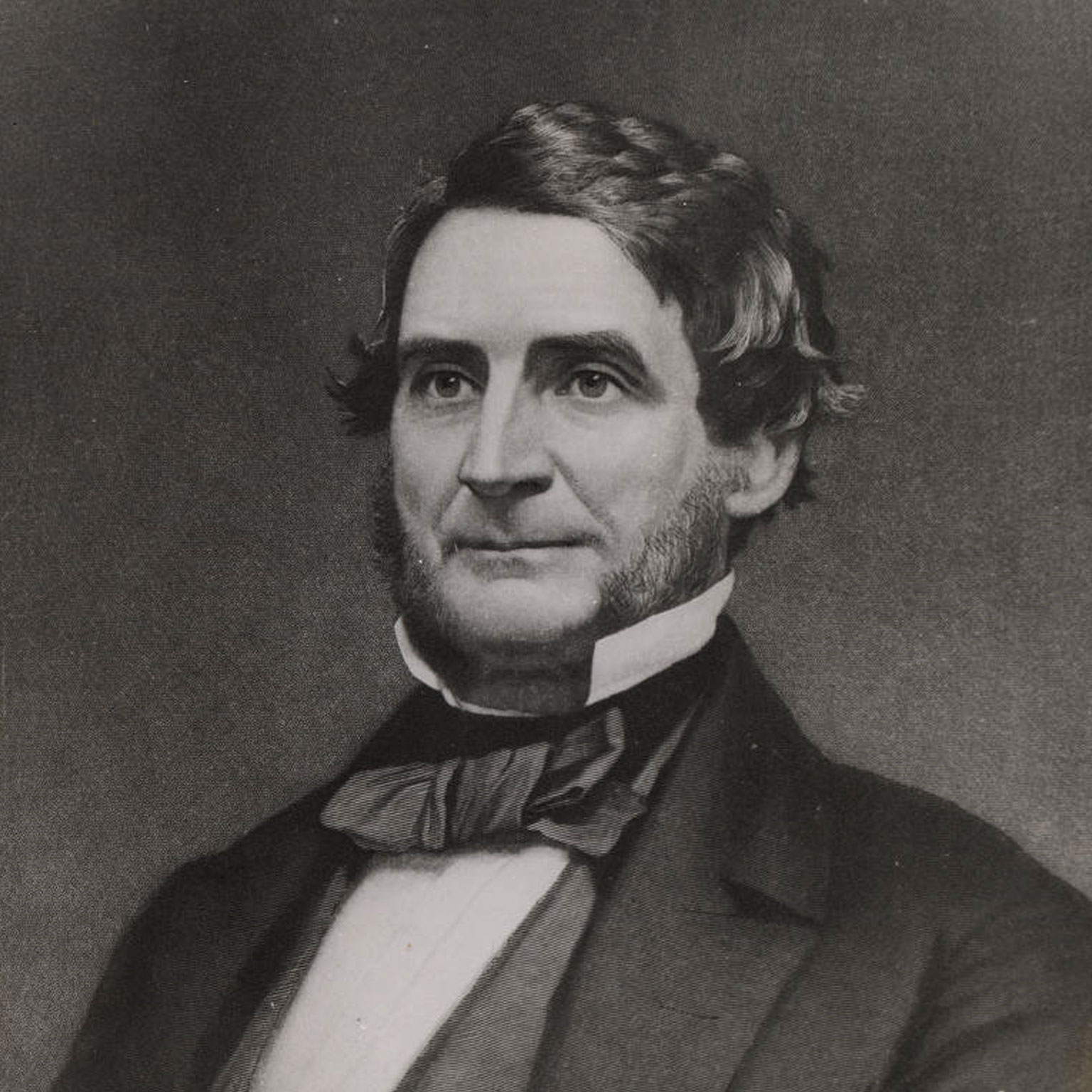

Asa Packer

James Audubon